Banner image is of the Don Roadway looking north by Riverdale Park in 1910. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library.

Wednesday, May 11th, 1887 dawned a perfect spring day in Toronto. Warm and dry, it was as good a day as any if working outdoors was your lot. And for one labourer, digging a garden on Smith St near Broadview, it was just that.

But as it would turn out, the man’s shovel was destined to turn up more than just sod that day. It would, in fact, unearth two human skulls.

Now, while there is no doubt that this came as a fair surprise to the labourer – I know it’d have shaken me down to my boots – it wasn’t the first time human remains had been found in the area. Less than a year before, in June of 1886, a 15th century Iroquois settlement and ossuary, containing the remains of more than 100 individuals, was discovered just one block north on Withrow Ave:

So you can imagine that the discovery of two skulls a year later might’ve been a tad less surprising than you might expect. But here’s the thing – right off the bat something pointed to the idea that the two skulls might not have been part of the Withrow ossuary:

… In a tin box?

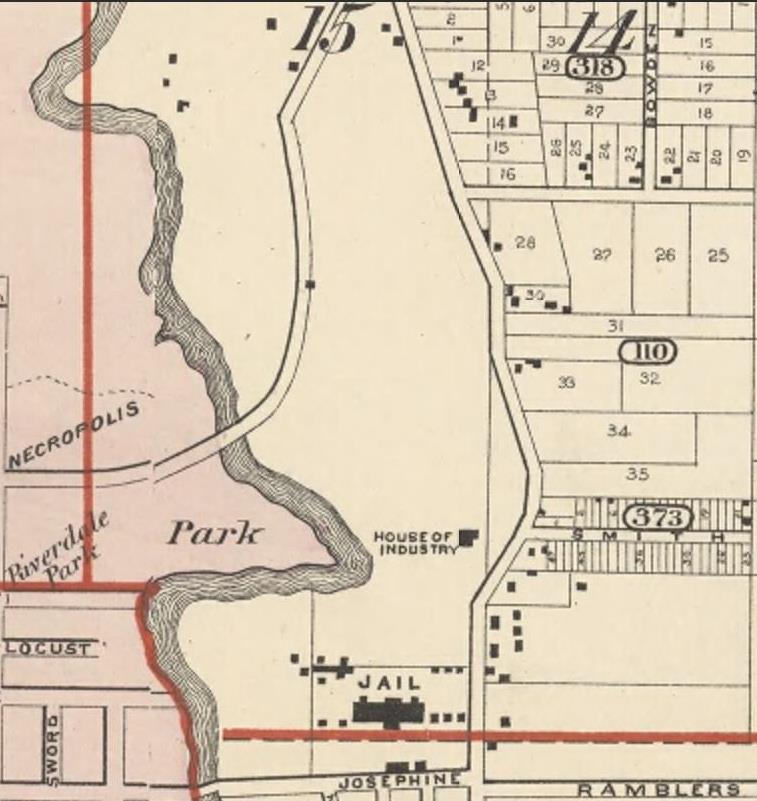

Well, I don’t know about you but the number of questions this raises is almost more than my inquiring mind can bear. For starters, was this a crime or a memorial? Is it possible someone reburied skulls from the Withrow ossuary as some kind of token gesture? Could it somehow be connected to the House of Industry turned Small Pox hospital which sat very near Smith St in the 1880s? Or, for that matter, the Don Jail just south of the site?

Who would’ve done this, and when? And, most importantly, whose skulls were these?

So I started digging (no pun intended – okay, perhaps subconsciously), hoping to find some answers. And now, after what feels like ages spent searching, I’m sorry to say that our best clue in this mystery – the tin box – appears to have disappeared behind the frustrating fogs of time – taking the smaller, crushed skull with it.

But – and I hope this is some small consolation – I can tell you what became of the remaining skull.

Our story begins, of course, with the labourer.

Though the news clipping makes it sound as though he was a solitary soul working at a private residence, in actual fact, he was one of hundreds of men working at a construction site. At the time of the discovery, the area was under development and there were no houses yet built where he was working on the south side of Smith St (today’s Riverdale).

Of course, if such a find were discovered today, the site would’ve been shut down and the coroner called in, followed by the archaeologists. But nothing like this appears to have happened that day in May. Now, you may be thinking “well of course not, it was 1887.” But actually, even though it was early days for what is considered “scientific” archaeology, there were some local scholars keen to make a proper report of such sites. The earlier discovery on Withrow for instance, uncovered by the very same development work, did result in an archaeological report (albeit a kinda slapdash one) by David Boyle – so certainly such things were not unheard of in 1880s Toronto. Though as we learned in Weston, as late as 1911, some early Indigenous burying grounds were still being treated like this:

Anyhow …

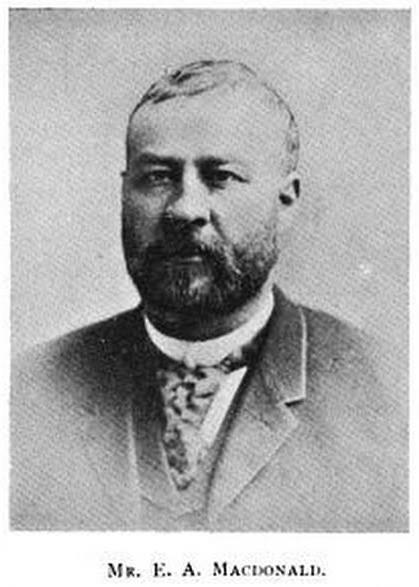

Rather than following anything like what is now considered proper protocol, the skulls in the tin box followed this route instead: the labourer gave them to the construction foreman who in turn gave them to his boss, the real estate developer and alderman Ernest Albert MacDonald:

Ernest MacDonald was born on November 1st, 1859 in Oswego, NY – though soon after his family would move to Brockville, Ontario. As a young man he came to Toronto where he received a general education and then it was on to Kingston for military training. After that, he returned to Toronto and promptly dove into real estate, which had become a gold mine during the building boom of the 1880s.

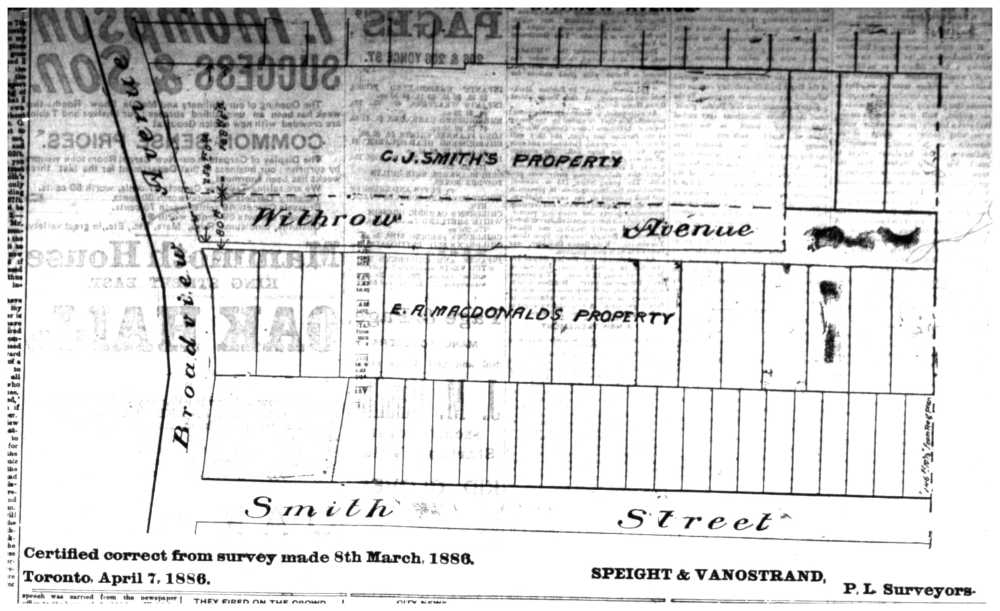

And ol’ Ernest certainly had a knack for the business. Focusing his attentions on undeveloped areas east of the Don River, he became best known for building up the suburb of Chester (today’s Chester and Danforth neighbourhood) as well as Riverdale – the site where the ossuary and tin box would be found – paving roads, digging sewers and erecting large, handsome homes in each.

Here we have the Riverdale site as surveyed for his development plan in March of 1886:

But like oh so many other enterprising businessmen before and after him, MacDonald felt the pull towards political office. Throughout the mid-1880s and early 1890s, he succeeded in becoming alderman in both the St. Matthew’s and St. James’ wards – on separate occasions, of course. He would even win the mayoralty once – on his fourth try – in 1900.

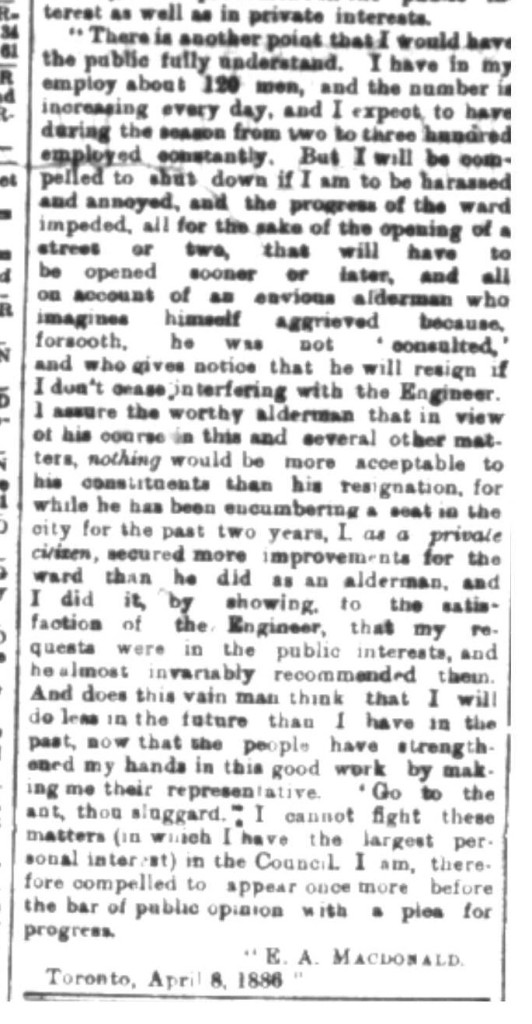

But somehow, despite being elected to these posts, MacDonald always managed to skirt real popularity. Neighbouring aldermen would start public spats with him – taking issue with the costs and plans for his developments – and MacDonald would respond with lengthy, defensive letters to the newspapers that I doubt won him many friends. I’d post one here, but really they’re so painfully long and prickly that I don’t think you’d thank me.

… Okay fine, here’s a portion of one:

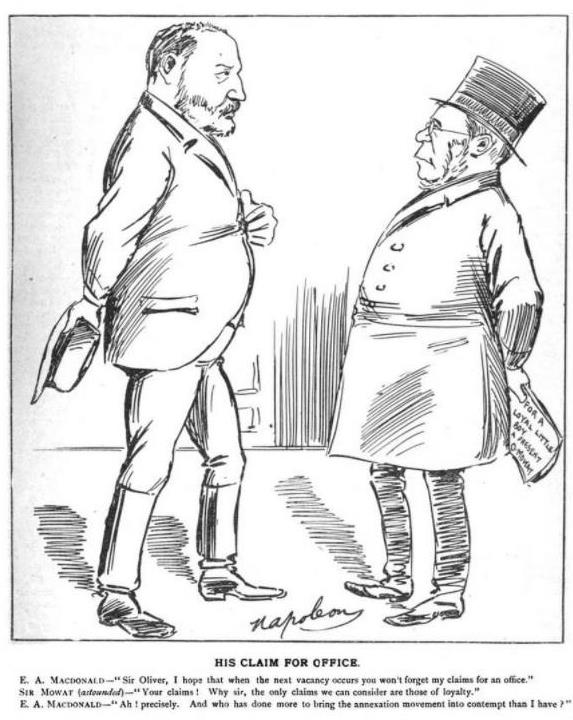

But perhaps his greatest sin, at least in the eyes of his detractors, was MacDonald’s support for annexation. The movement to leave Great Britain and take up with the United States had been around since the American Revolution, but it burned especially bright in the 1890s. As you can imagine, MacDonald’s public support for the movement made him pretty unpopular with the fierce loyalists (AKA pretty much every bigwig in Ontario.) But at least the humour guys over at The Grip seemed rather fond of old E. A. – at least insofar as they could make sport of him:

And so we have the man who found himself in the rather unique position of deciding what to do with two human skulls in a box.

What MacDonald decided to do, for good or ill (ill, definitely ill) was separate the two and make a gift of the larger, complete skull to a newspaper editor named Louis P. Kribs.

Why he chose Kribs, I’ve no idea. Well, that’s not exactly true – I’ve some idea why he might’ve. For one thing, they were both staunch Liberal-Conservatives – don’t let the “Liberal” fool you, that’s merely decorative – and Louis Kribs was one of the best known supporters of the party at the time. So, at the very least, they moved in the same circles. Also, as Kribs was editor of the popular Toronto News, I think it’s possible MacDonald thought bestowing such a unique “gift” on him might gain him some sympathetic press for once.

Whatever the reason, the skull was passed on to Mr. Kribs.

Now this is the portion of the post when I would normally show you a photograph or, at the very least, an illustration of Louis Kribs. Alas, as of press time (ha), I have yet to find one. For a time I even imagined he was one of those rare creatures who’d managed to elude the camera, but I now know that not to be true:

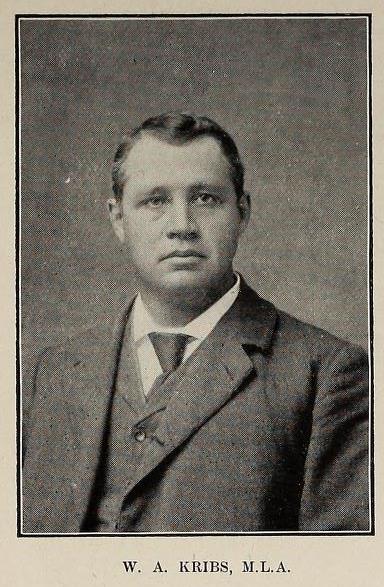

But here’s what I can tell you – he was big, blonde and described as looking like “a German comedian” (I know, good luck with that one). And if it helps, I do have a photo of his brother, William, who seems to fit the same description fairly well. Though one or the other might’ve had something to say about this. Anyhow for what it’s worth, here’s his younger brother William:

Also, Louis was apparently quite the fashion plate:

But enough of his looks – let us learn about the man himself.

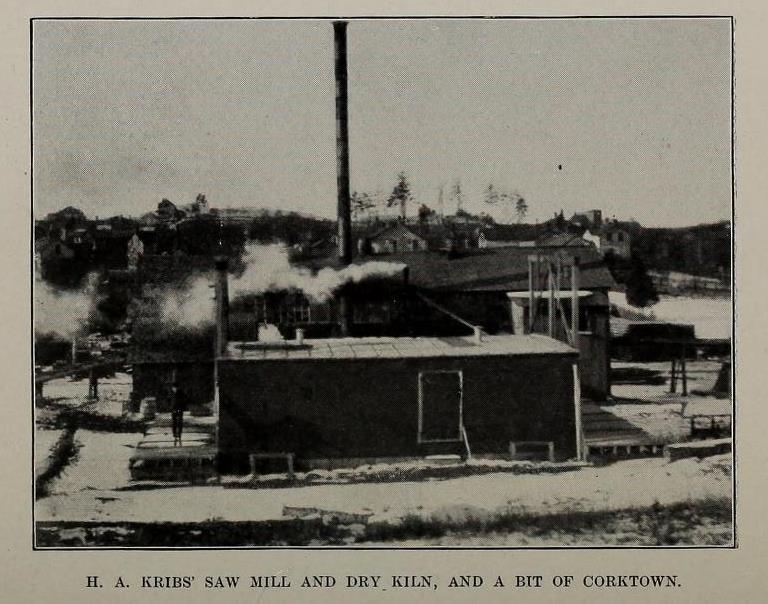

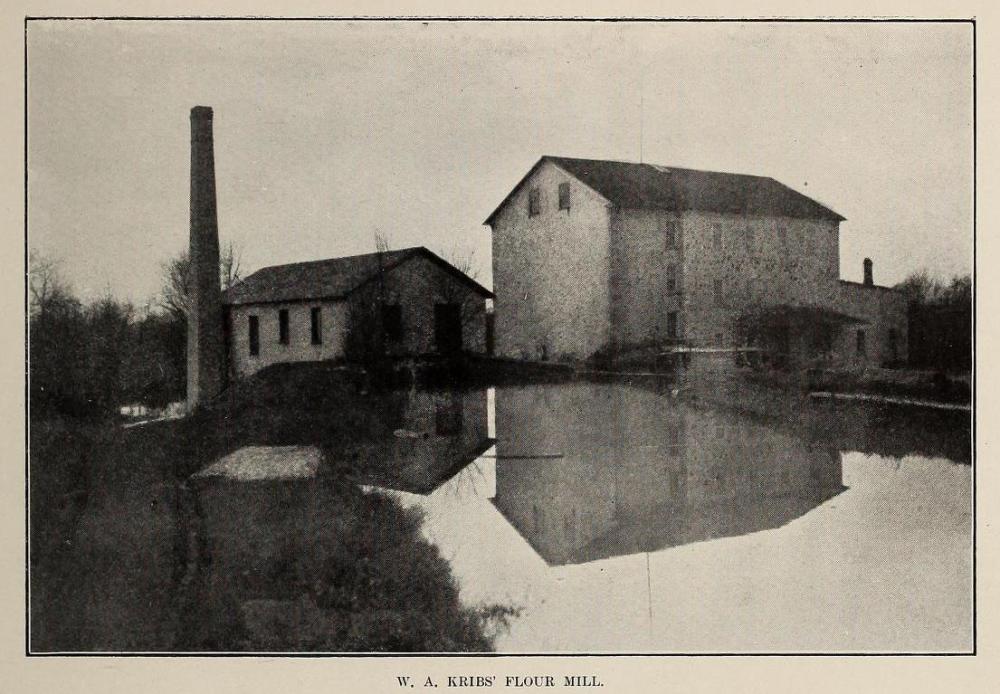

Louis Kribs was born on February 27th, 1857 in Hespeler, ON which is now an area within Cambridge. His family, which was of Pennsylvania Dutch-stock, were early founders of Hespeler and claimed a large presence in the town, running both a flour and lumber mill.

Here we have some somewhat scenic views of their holdings in 1901:

But, despite all this at his fingertips, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that Louis’s plans never involved staying and working in any of the family’s businesses in Hespeler. From the get-go he seemed more interested in making his own way in the world.

As a teen, he set out to work in the lumber camps north of Barrie – which, when your family owns a large lumberyard, is already making something of a statement. But by the mid-1870s, he felt that writing might be more in his line (life at a lumber camp would do the same for me) and so set out for Toronto and the offices of The Globe. Luckily for Kribs, the Globe’s editor George Brown decided to give him a shot. After that, it was a steady rise for Louis Kribs, newspaperman.

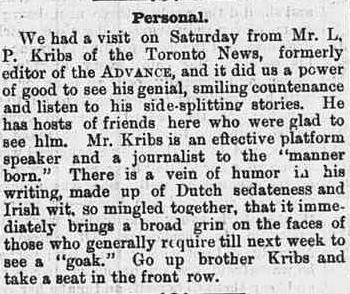

In 1882, Kribs left The Globe – wooed by Barrie’s Northern Advance and the opportunity to act as editor. Though he’d stay just over a year, I don’t believe he ever cast a greater spell on a community. When he left Barrie to take on the Walkerton Herald, there was nothing but good cheer for the man. A collection was taken up and they wined and dined and made speeches at him, which they later regaled their readers with. And when he stopped in to visit the old gang years later, they wrote about that too:

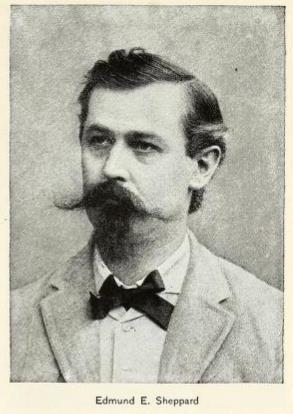

But Walkerton couldn’t hold him for long either and by 1884 Kribs was headed back to Toronto. This time, however, he would find himself in much livelier company than that at any other paper. This time he was going to work for a first-rate character named Edmund Ernest Sheppard:

As you might’ve gathered from his photo, Edmund Sheppard had a certain flair. Though born and raised in Ontario, he’d spent what were (quite apparently) his formative years cowboying out in Texas and Mexico, and so came back with a whiff of Buffalo Bill-ness about him. Not to mention a taste for chewing tobacco, whiskey and rough language. And his paper, the News, was something of an extension of this out-sized persona.

Unlike other Toronto newspapers of the time, the News specialized in punchy headlines, serialized novels and a lurid gossip column called “Peek-A-Boo.” According to one former reporter, Hector Charlesworth, there was even a gimmick aimed at kids:

“For a time he printed it on pink paper; and when I was a youngster, most boys desired their fathers to take the News in order that they might have pink kites.”

The paper’s office, at 106 Yonge was a fitting setting for such an outfit. Hector Charlesworth remembered it as a “a curious rookery” where there was “a platform or balcony on the second floor where you might stand unseen and watch anyone moving about in a corridor below.” That might seem like an odd thing to mention – the ability to watch someone without being seen – but Charlesworth remembered it for a very good reason.

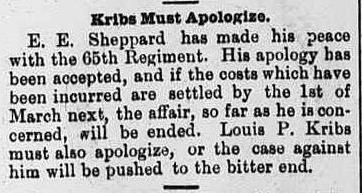

In 1885, towards the end of the North-West Rebellion, someone sold Kribs on the phony story that the 65th Battalion out of Montreal (which was largely made up of French Canadians) had “shirked their duty” out of sympathy for Louis Riel.

Now, Louis Kribs may have been the most genial of men, a gifted storyteller and writer, and a mighty fine dresser but he apparently had one shortcoming that folks remembered – and that was a certain cavalier attitude toward such things as, you know, verifying facts. And so he wrote up the libelous tale about the Montreal battalion and Edmund Sheppard printed it, sight unseen.

Well, the officers of the 65th brought libel charges against the News, naturally, and Edmund Sheppard found himself taking responsibility for the article, having printed it without reading it first. But, noble as that is, it didn’t mean he planned on being there when the warrants were served. And so you see where that trick balcony came in. Supplementing this look-out, Sheppard also knocked holes in the office’s walls as a means of quick escape should he ever have to make a fast get-away.

Oh what a time it must’ve been …

Anyhow, it would take almost two years, but eventually they got him – and Kribs:

All things considered, Kribs got off fairly easy. Ernest Sheppard, however, bore the real brunt of Kribs’s article. The “cost incurred,” as mentioned above, was a smallish sum of $500, but the scandal eventually brought an end to the Toronto News.

And as the paper closed up shop, Kribs packed up his various items including the Smith St skull which he had hung, like an ornament, above his office door.

The News might’ve failed but Louis Kribs’s popularity sure hadn’t worn thin – within a few weeks, he was named city editor of a new paper called The Empire:

This same article would go on to mention the quality of the Empire’s printing presses, and the expertise of its printers:

And while this may not seem very interesting, and you might be wondering why I’ve taken this turn (hopefully only for the first time), it’s the breadcrumb which leads to the third man in our story. Because in 1892, when Kribs was leaving the Empire after it merged with the Daily Mail, he gave the skull to a printer named Solomon Cassidy.

Now Sololom Cassidy (or Sol, as he preferred it) was no Ernest MacDonald or Louis Kribs – his name was not well known, except in the Typographical Union, where he was president of local 91. In his work at the Empire and, later the Globe, he made a career of laying out the stories of other notable people, but his own was never told. Despite that, I can tell you a few things about him.

Cassidy was born in Toronto in the 1850s, the son of a turnkey (jailer) named William and his wife Sarah. William worked at the Don Jail alongside his brother Solomon (our Sol’s namesake, I’m assuming), who was the resident carpenter.

In the early 1860s, the family lived on Berkeley but within a few years moved to 15 Matilda St – in what is now Riverdale – not too far from where the skulls were found. After William’s death in 1874, our Solomon Cassidy – not his uncle – would continue to live on Matilda with his mother Sarah, until her death in 1913.

Sadly, there is nothing left of the Matilda St that Sol Cassidy knew. All the original houses were torn down in the 1960s, as part of some misguided improvement project, leaving nearly 180 homeowners fuming. But here’s a view of what the street, very near Sol and Sarah’s place, looked like:

As to whether Sol kept the skull here on Matilda, or among the presses at the paper, I couldn’t tell you. But, I do know that after almost 18 years of keeping it, he finally chose to give it to the University of Toronto in 1909. And from there, it entered the Royal Ontario Museum’s collection.

Throughout all of this – from the initial discovery of the skulls in 1887 to the single skull’s entry into the museum’s hands – I can’t tell you what its various “keepers” thought its origins were. But it appears, because of the earlier find on Withrow, that it was assumed to have also come from an Indigenous burial – somehow, at some point. Certainly, I believe Kribs thought this when he hung it over his door. As we can see from the Weston discovery in 1911, it was considered quite acceptable to dig up Indigenous burials and treat the bones as curiosities in a way that would never happen with a European burial.

But who was this poor soul whose skull was carted all over town?

In hopes of settling this question at least, I went to the museum looking for an answer. And though they were very kind, they were very firm in turning me away. While they could confirm that the skull is still part of their New World Archaeology collection, they could not tell me anything about it under museum policy which restricts information regarding human remains and burial practices – unless I could prove that I am a descendant of the individual. Which would be a neat trick considering they can’t tell me who it is. But anyway …

Of course, the larger story here is the exceedingly problematic issue of museums keeping remains and items sacred to Indigenous peoples – something the Toronto Star wrote about quite recently. Though it appears that the ROM, in a refreshing break with the past, is opening up to returning artifacts in their collections to their rightful homes.

Unfortunately, I don’t know that such a day will come for the Smith St skull. In archaeology, context is everything – and so a skull which was likely buried twice before being plucked from the earth, separated from its companion, and removed from the tin box which was the lone clue to its story, is farther from home than most.

But I hope that’s not so. I hope it will one day make its way back to where it belongs.

The end of the three:

Ernest Albert MacDonald was bankrupted when the building boom went bust. However, he would go on to serve one, very unpopular, term as Mayor in 1900. In his defense, it’s thought that during his mayoralty he was already off his head from the effects of Syphilis. He would die of the infection, at 44, in 1902.

Louis Pannabaker Kribs died, at 41, on March 24th, 1898 of a stomach hemorrhage while visiting in Ottawa. His loss was mourned by all journalists, and across all political parties.

In contrast with MacDonald and Kribs, Solomon Cassidy lived to a ripe old age – about 80 or so years old. As late as 1936, he was living on Delaware St and still listing himself as a printer. Though for his sake, I hope he’d been long retired.

Note: I have titled this “The Fourth Man” in reference to the skull with no identity, though I’ve no idea whether it is actually male or female. I’ve based the title, very unscientifically, on the fact that it was the larger of the two found – but realize that size is but one consideration of many when assessing the sex of a skull.

A great read Katherine

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Reggie!

LikeLike

An odd and amazing mystery … and I love all that you untangled. (And, printing a newspaper on pink paper to entice kite-making children is sheer brilliance, you know.) Thank you for always taking us to such interesting places in your world! You’re one of the best. Truly. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, thank you Jackie! I’m really glad you enjoyed it. I’ve been stewing over this one for a good long while and had hoped to have more answers to share, but I’m hopeful there will be a Part Two in the future. 🙂

LikeLike

What a cast of characters. Your thorough detective work has woven together an intriguing story – and dealt with some ethical issues along the way. Who owns the past?

And there’s that Kribs fellow – the “German comedian” – with origins close to where I currently call home. Makes me want to go poking around Hespeler for the evidence. Thanks for another great read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aren’t they a wild bunch? I’d love to have been a fly on the wall at the News when Edmund Sheppard and Louis Kribs were holding court. By all accounts, they were a couple of live wires.

I thought of you often as I was researching Kribs’s youth. If you ever do get poking around Hespeler, I’d love to hear what you find. And honest, I’m good for that $20 if you ever stumble on a photo of the man

Thank you, as always, for joining me on these trips through old Toronto.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure!

LikeLike

nice

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome…:-)

and you can visit my blog too…;-),

inspiringdude.wordpress.com if you find something intrusting then Don’t Forget to follow my Blog…:-)

Keep in touch…:-)

LikeLike

For some reason, I read the caption on the banner image as being of “Don Roadway”, as in, I actually thought there was a man called Don Roadway in the picture, and I thought, “Wow, that’s an unusual name.” Got it now though. I would actually probably be pretty excited if I found a human skull (but not a human head, something about the flesh makes it creepy), but I don’t think I could treat a whole heap of them in what is clearly a burial ground quite as cavalierly as those children. Your description of “Liberal-Conservatives” made me snort with laughter (unlike that cartoon, which has to be the least-funny cartoon I’ve ever seen, though your caption was a treat). Liberal sure didn’t have the same meaning back then!

It’s a shame the museum couldn’t give you any answers about the skull (especially since there’s no way that any direct descendants could still be alive. There’s a skeleton in the museum where I work, but since he’s a Saxon, he’s not really contentious and we just have him out on display), and also a shame that the tin box disappeared. It’s an interesting story nonetheless, particularly the way you tell it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! Don Roadway, the man. I like that. Sounds like a character in some ‘60s TV show.

Yeah, in all honesty, I wouldn’t mind stumbling on one myself if, like this, it’s clearly a reburial and there’s some mystery to it. That’s what makes me crazy about this one. I don’t know how everyone just shrugged their shoulders and didn’t seem to question how it came to be there. The only other person who’s seemed remotely interested in it was an archaeologist who wrote a small piece about it in the 1980s. At that time, the skull had been given to an anthropologist for examination. Unfortunately, that anthropologist has since died – so I couldn’t contact her to find out what she learned. I was hoping the museum would be able to share something about her report with me but, pfft, nothing. Of course, what I’d really like to see is the tin box itself, but I have a feeling that E. A. MacDonald character tossed it out at some point. Ah well …

Anyhow, I’m really glad you found this interesting too – it’s nice to have someone to share this weird story with!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Solid, Katherine. Gotta get to Toronto one of these days and pick your brain about all the things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nick! I’d love that.

LikeLike

Another great piece. I was curious to see how it would all come together in the end and you pulled it off. Bravo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I’m really pleased you think so. I had hoped for more answers but, of course, the trail’s pretty cold at this point. Hopefully, with a good bit of luck, I’ll have reason to revisit it one day.

Oh! And I’ve started digging into Gifford St. Thanks for putting me on the scent. Hopefully I’ll have something fun to share soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very excited to read what you find out! There are so many nooks and crannies and hidden histories that so few people know about. I have a great time reading your blog. I don’t think anyone else is approaching Toronto’s history in quite this substantive way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My goodness – that means a lot to me. Thank you! (And apologies for gushing so much.) I started this with the belief that there’s a good story hidden on every block. And, so far, the good, old citizens of Toronto have not disappointed me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel the same way about the world. I think everybody’s got a great story in them, just as every block and neighbourhood has in Toronto, it’s just that most people don’t know how to tell these stories. I’m an avid reader about Toronto’s history, though I didn’t move here until 1988 after high school north of the city. I’m glad we have people like you on the case to preserve the history and also to entertain!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! What a fascinating read and the questions it poses about who does own the past-and who can claim it poses all kinds of interesting (and ethical) thoughts-terrific research/detecting!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so happy you enjoyed it! Yes, the mystery of this skull, and all the tricky questions it raises, had me stewing for quite some time. I’d hoped to uncover more answers, but I’m hopeful there’ll be cause to revisit this tale one day.

LikeLike

K Tylor, any luck on finding the photo of Louis Kribs?

LikeLike

Sorry K Taylor 🙂

LikeLike

Sadly, no – and it truly pains me. 🙂

LikeLike

I came across this article when doing research into ancient remains found on Withrow Ave in January 2024. I think it’s safe to say, this is yet another example of “our home on native land”. https://toronto.citynews.ca/2024/01/06/human-remains-found-withrow-avenue-toronto/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, indeed!

LikeLike