Banner photo is of Sherbourne and Queen looking west on May 4th, 1917. From the City of Toronto Archives.

I grew up in the west end of the city – almost smack dab between Dundas West and Lansdowne, near Bloor St. If you know the area, I wonder what you think when you hear those names. Especially if you’ve known the area over the past couple of decades.

Well, I can tell you that when I was growing up Dundas West felt solid and bright, whereas Lansdowne was, well … let’s not mince words – Lansdowne was rough. Yessir, it had a pretty good dose of grit back in my day (I swear I’m not sitting in a rocking chair, whittling wood.) For me, this gritty feeling was cemented in a bar called Ciro’s * which in my mind acted as the western limit of the neighbourhood. It had a reputation for hard-drinking and as my Dad would often say, a man was thrown through the window every night. That sounds like one of his little jokes but I often saw the large front window boarded up. Walking east from Ciro’s, the tone held and things felt a little dicey till you reached Dufferin.

So you can imagine why I found it funny when I learned the street was named for the Marquis of Lansdowne. Specifically, the 5th Marquis, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, who’d served as Canada’s fifth Governor-General. Holding the post from 1883-1888, he’d be present for a rather lively period which included the North-West Rebellion, as well as the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway – which he personally rode to its western end in Vancouver, becoming the first Governor General to do so.

Anyhow, while I hadn’t much interest in him at the time (or really marquises in general), it took some tricky mental gymnastics to replace the associated image of Ciro’s boarded-up front with a member of the British peerage. (Similarly I had issues with Simon and Garfunkel’s song Scarborough Fair when I was kid. Herbs and cambric shirts – never mind a fair – were the last things I connected with Scarborough, Ontario. (Sorry Scarborough, that’s my Toronto showing. I promise I don’t think it anymore.))

About now you’re probably thinking, hey lady, the title of this piece says Moss Park … Right you are. I’ve brought all this up because Moss Park is a great example of a name that has come to mean something quite different to Torontonians than originally intended.

In the early 19th century, when it was first named in honour of moss (apparently) the land was almost unimaginably lush and idyllic:

Today the area is markedly less green and there’s no sign of the brooks or stream which once passed through the grounds. There is, however, a fair sized park on the north side of Queen, between Sherbourne and George, which carries on the Moss Park name. But, though it features a baseball diamond, tennis courts and a community centre, it doesn’t do much to dispel the reputation of a rough, troubled neighbourhood.

This reputation, fostered for half a century, was born of the poverty brought by de-industrializing the area in the 1970s, and is cemented in the numerous homeless shelters in the neighbourhood – more than you will find in any other one area of the city. While I’m sure there are many who blame the shelters – if you’ll pardon me, I’m just going to climb up on this soapbox – they really are just a reflection of the inequities within the city itself. Something that’s becoming more evident as luxury condos move in and squeeze the vulnerable out. If more shelters and health services were spread across Toronto (not to mention affordable housing) it’d go a long way to relieving the pressures on this hurting area. … Now, if you’ll just give me a hand, I’ll get off this thing and get back to my story .

Anyhow …

The early days of the area played out a bit like a hot-potato game. Known originally as Park Lot 5, the large parcel was first granted to William Osgoode in September, 1793 by John Graves Simcoe. Osgoode lost his right to it, possibly because he was a non-Resident, and the lot was given to Deputy Surveyor General David William Smith in March of 1798. He managed to hold onto it for a bit, but like Osgoode before him, eventually headed back home to England and so he transferred the land to Duncan Cameron for £500 in March of 1819. Cameron, much quicker at his turn with the potato, turned around and sold it to William Allan within a week – for the same £500 price tag.

The lush 100-acre park lot, which Allan named Moss Park, ran from Britain St (just below Queen) north to Bloor and spanned George St to Sherbourne.

The official story is that William Allan named the estate for the moss which covered the family home, but considering that he was born in a place called Moss, Scotland you can’t help but think there might be another explanation.

In any case, Allan was born in Scotland in the 1770s and came to Canada as a young man, working as a clerk for Forsyth, Richardson & Company. The company appears to have dealt in pretty much everything from furs to real estate to that all important beverage, tea:

In 1795, he came on to York (Toronto) and within two years had opened a general store with Alexander Wood. Not to undersell my own subject but Alexander Wood is actually a much more interesting story. Scandal-plagued in the early 1800s, he is now embraced as a gay hero and commemorated with a rather lively sculpture in the Gay Village at Church and Wellesley – the area having been part of Wood’s original property. Other than the Winston Churchill at City Hall, it has the most personality of any public figure’s likeness I’ve seen.

My, how I do digress …

After Allan and Wood’s partnership ended, Allan kept the business and did very well. In 1800 he became a justice of the peace and the district treasurer. If you can believe it, in the same year he also became collector of customs and district inspector of flour, potash, and pearl ash (an ash, I was previously unaware of.) Were that not enough, he also took on the duties of treasurer of the Anglican parish, warden of the church and became the postmaster. A member of the militia, he was made major of the 3rd Regiment York Militia during the War of 1812.

During the war, Allan also kept busy by selling goods to the garrison. This little endeavour would prove immensely profitable, as he raked in almost £13,000. Though when you consider that, as a member of the commission which processed claims for losses suffered during the war, he authorized his own request for compensation – you realize the amount of money he received was likely a good deal more.

If you’ve visited here before and have met some of our other early townspeople, you might be thinking “Hey, the Family Compact must’ve loved this guy.” And you’d be right! Oh yes, ol’ Bishop Strachan (the Compact’s patron saint) and William Allan were very chummy. Together they worked closely to establish the Bank of Canada, of which Allan was made president.

While I could probably go on listing his stuffy accomplishments for a while yet, I think instead I’d rather share W. H. Pearson’s delightful recollection of Allan which, in my opinion, brings him to life more vividly than anything else:

“Mr. Allan was a dignified, military-looking man, rather brusque in his manner. He had a strong Scottish accent and when asking for his letters, when I was a clerk in the Post Office, used to say to me, “Boy, boy, oighty-oight, oighty-oight,” this being the number of his letter box, next to Bishop Strachan’s, which was eighty-seven.”

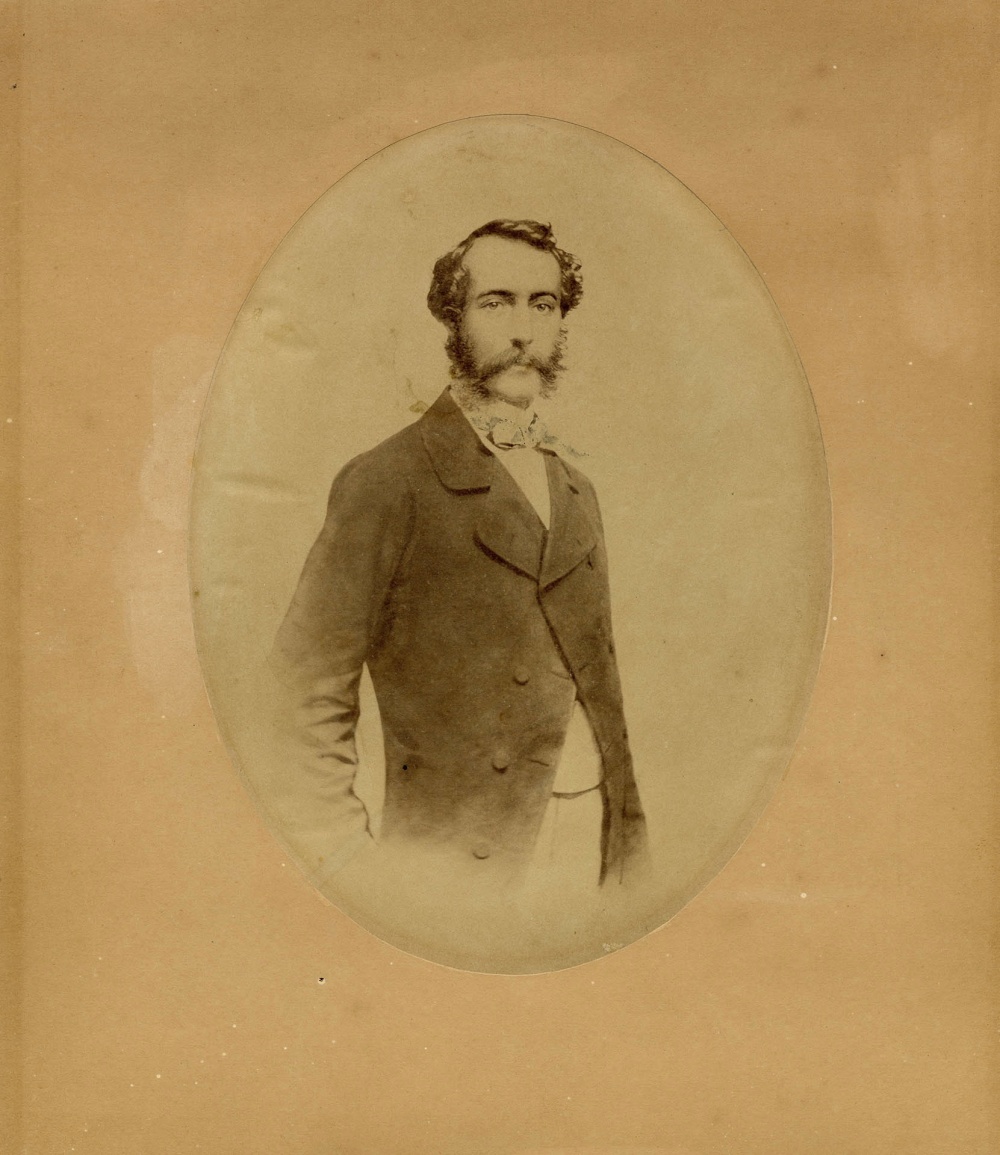

William Allan died on July 11th, 1853 and with his death Moss Park became the domain of his son, George William Allan:

George, like his father before him, would become a big name in municipal dealings; first as an alderman, then as the 11th mayor of Toronto in 1855. He’d eventually become a member of the Legislative Council and then a Senator. All fairly impressive accomplishments, yes, but I’d wager for most Torontonians he’s best known as the man who gave the city its beloved Allan Gardens.

Unlike his father (at least from what I can tell), George was a big believer in the Arts, presiding over the Ontario Society of Artists and the Toronto Conservatory of Music. He’s also remembered for commissioning one hundred oil paintings from the artist, Paul Kane for $20,000. As you might imagine this was a pretty good chunk of change in 1852 (hell, I wouldn’t sneeze at it in 2016) and it allowed the remarkable artist to be just that – an artist.

In 1854, with the population growing and development spreading around him, George Allan had much of the Moss Park land separated into lots and sold.

By this time, a number of small wooden homes and businesses were already cropping up along the east and west perimeters of the estate – Caroline St (today’s Sherbourne) and George, respectively. By comparison, the stretch between the two, along Queen, was sparsely populated. In fact, from the early 1850s to 1869, there were just two names listed as residents of the block: Thomas Storm and his son, William. Though the Storms were not landowners like their neighbours the Allans, they did as much – likely much more – to shape the Toronto landscape.

Thomas Storm was born in 1801 in Winteringham, Lincolnshire, England where he trained as a joiner and carpenter, and eventually rose to become a master builder. He came to Toronto around 1830 and soon partnered with Richard Woodsworth and Alexander Hamilton (note: not the American Founding Father currently on Broadway) to construct the buildings of the New Garrison. On his own, he would go on to build such remarkable buildings as the Gooderham & Worts malt house and kiln, and the Kersney House.

His son William meanwhile, who had apprenticed with his father, would bring the Storm name even greater recognition as one of Toronto’s most prolific architects.

In 1865, William Storm moved out of the Moss Park area and settled in the Romain Buildings at King near Bay. His father, Thomas, remained and did not give up his Queen St home until he gave up the ghost in December of 1871. As recounted in the History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario, at his death Thomas Storm had been “universally respected by all, having contributed no small share to the substantial growth and present prosperity of Toronto.”

With the Storms’ departure, their stretch of Queen became home to a handful of factories including the Dominion Tin and Stamping Works, the Ewing and Company Moulding Factory and the Ontario Lead Works. Well, as they came, so they went and by 1890 they’d been replaced by a row of handsome brick storefronts. Not long after they bloomed at the west end of the block, a hotel called the Kormann House was raised on the east corner in 1897.

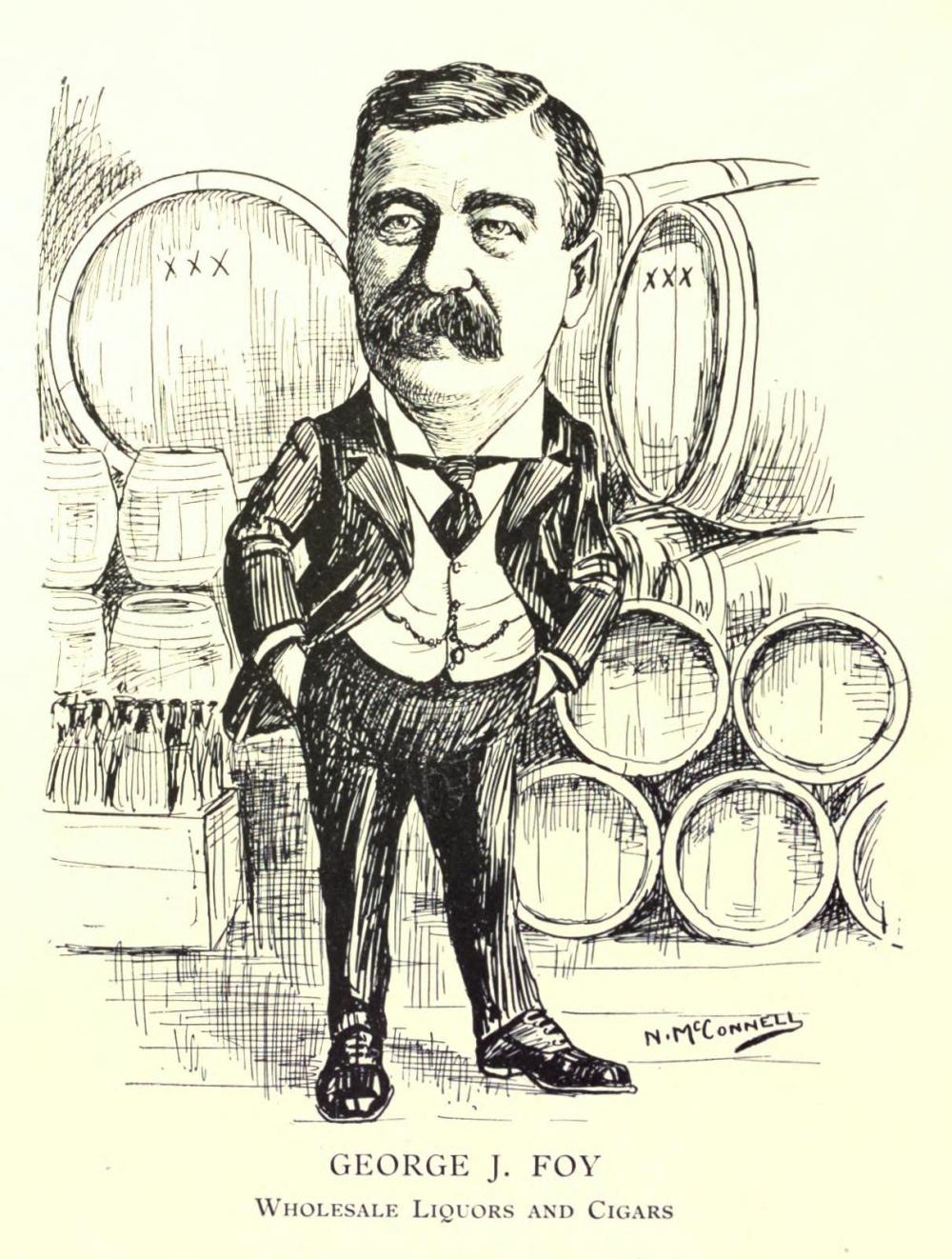

The hotel was built for a man named George J. Foy who did big business dealing in wholesale liquor and cigars.

Though he was apparently quite a big shot, the hotel was named for its keeper, Frantz J. Kormann. Like Foy, Kormann had ties to the booze business, being the son of Ignatius Kormann who’d founded Kormann’s Lager – a going concern in the city for some time.

At this point I wish I could show you – or at least tell you – that the Kormann House Hotel had once been a smart, inviting place to spend an evening. But I’m afraid the proof of it eludes me. In fact, the closest I can get to a photo of it in its heyday is in the background of this rather dispiriting photo.

But I can show you the way it has appeared to Torontonians for way too long now.

For at least a decade it has been boarded up like this, awaiting some unknown fate. Several years back there was a lot of talk about it being incorporated into a condo development and there’s even what appears to be a sales office adjoining it on Sherbourne. But year after year, nothing happens – though it occasionally gets slapped with a new coat of paint as if to prove it hasn’t been forgotten.

For all that has come and gone in the area, it’s this building which I most connect with Moss Park. Passing its blind windows day after day it’s become, for me, something of a symbol of the neighbourhood itself – beautiful in its bones, but sorely neglected. I sincerely hope that it will be returned to the community with renewed life and greater purpose.

* Note: Lest I inflict any damage on its current reputation, I’m happy to say that the rough and tumble Ciro’s of my youth became a great spot for Kung Pao in my late teens, and my mother and I stopped in frequently. I imagine it’s been some time since the glass-repair folks have been by.

Another really interesting post! I always love the photos and other artifacts you find to go along with them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you enjoy them! I have a lot of fun digging them up and discovering new things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No picture of the Alexander Wood sculpture? (Pauses to google it). Ah, yes, if it’s the one of him wearing a coat with bad-ass lapels, it is very characterful indeed. Your comment about the Churchill statue puts me in mind of the Roosevelt-Churchill bench on Bond Street, which is probably my favourite statue in all of London. I sat in FDR’s lap once for a cheeky photo. R.J. Edwards is a bit of a looker, I agree, but I think old George Allan is probably more my type, all thin and mustached as he is. And speaking of that haunted dollhouse, it would be ok with me if the exterior of it looked like Victoria College. 🙂 Excellent building.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! You got me – I’d planned to take a photo of the Alexander Wood statue (it’s really something else) but frankly, it’s been so stinking hot I lost enthusiasm for the idea of crossing town to get it. Yeah, George Allan was not too shabby – his moustache was glorious and he had kind eyes. To be honest, cute as I think he was, I can’t decide if Edwards was actually that handsome or just the best guy in the picture. I mean, it’s pretty slim-pickings in that crowd, looks-wise. Oh my god, a haunted Victoria College dollhouse? Yes! I’d never leave the house again.

LikeLike

A fascinating post,Kate. I didn’t know – or perhaps I didn’t take notice – of any of this. It’s interesting to learn how Allan Gardens got its name, for example, and the influence and achievements of the Allans and Storms. Great photos. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank YOU Cynthia – it does my heart good to hear you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your article would love to connect as revitilizing area- I own one of the storefronts

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I’m so pleased that you liked it! It’s truly a wonderful area – I’m so glad to hear it has you on its side. Please feel free to write me anytime at onegalstoronto@yahoo.ca.

LikeLike

George Foy was my great grandpa-and some of the little that I know about him, comes from your article so thank you kindly! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful to hear! You’ve made my day. So glad you found this post and that it’s added to your family’s story. Thank you for the kind note 🙂

LikeLike

I am having a very difficult time finding facts and information on the street I was born and raised on with only 10 house s on it, whole street torn down in the 50s The street name was Moss Park Place, any help or photos would be greatly appreciated. thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My sincere apologies for the late response. I will do some digging and let you know, via another response here, if I can find anything that will help you out.

LikeLike