Banner imagine is of Jordan St, looking north from Melinda to King, in 1907. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

In our last visits to Jordan and Melinda, we first met the streets in the 1830s as they emerged from the once private land of an American named John Van Zant, and watched as they grew from a quiet residential neighbourhood into the tony address of some of the city’s biggest movers and shakers of the mid-19th century.

We also discovered that through the decades, despite the area’s swift development, one of its first residents was said to remain. This, of course, was John Van Zant’s young daughter, Stella, who had died and been buried on her father’s land in the first decade of the 19th century. Her grave, protected by an agreement between her father and Jordan Post – the man who would next own the land – sat like a thumbtack in this dramatically changing streetscape.

While Jordan and Melinda of the 1850s saw the neighbourhood transformed by offices like James Lukin Robinson’s Wellington Chambers, the troubling and troublesome Indian Office, and Kivas Tully’s Victoria Hall, the 1870s would see the area dominated by manufacturers. The first of these – and arguably the most important – was the firm of Jacques and Hay.

Now, before I tell you about the founders and the company itself, let’s first sort out the pronunciation – because, most likely, it’s not what you’re thinking. Rather than having the French flourish you might expect, Jacques was pronounced “Jacks” and the two names were run together so that they became “Jacksenhay.”

Okay, now that we’ve got that settled, on to Jacks, er, Jacques himself:

Born in Cumberland, England in 1804, John Jacques studied cabinetmaking in a little place called Wigton before heading to London to pursue it as a career. By 1831, now 27 years old, he was on the move once more – trading England for New York. Whether he’d never intended to stay, or decided greener pastures lay elsewhere, I can’t say. But New York didn’t hold him for long and he soon landed here in York (Toronto) that same year.

After a couple of jobs with established cabinet-makers (one which left Jacques broke when his employer went bust), he eventually landed in the employ of a man named William Maxwell.

While Maxwell seems to have had a good thing going, he apparently wanted out because by 1835 he offered to sell his business to Jacques.

It was this proposition Jacques was mulling over one night when, as luck would have it, he bumped into another young cabinetmaker named Robert Hay:

Though there’s no word that the two had ever worked together before, I imagine York’s “cabinetmaking crowd” was a small one in those days and they likely knew each other’s work. In any case, Jacques mentioned Maxwell’s offer to Hay and asked if he’d be interesting in partnering. Hay thought it a fine idea – and so Jacques and Hay came to be.

Offering all household furniture, and even upholstery, their line had something for every everyone, as author Charles Mackay discovered in his North American travels:

Now, you’ve probably picked up on the fact that theirs was no longer a small storefront where the two labored over pieces personally. (If instead you can imagine a kind of Santa’s workshop outfitted with large, early industrial machinery, you’d probably be closer to the mark.) By 1856, Jacques and Hay was not only Toronto’s leading furniture manufacturer, it was also the largest industry of any kind in the city. Which is really something when you think about it.

Now, despite the large scale of their business, the quality of their products did not waver. If anything, the company’s name became the high watermark in furnishings and their work was heralded at every exhibition they showed at:

Naturally, this meant that everyone who was anyone wanted to be outfitted by them:

Before long they were being hired to completely outfit everything from private homes and schools to Masons’ lodges and even lunatic asylums:

… what’s that? Oh right, of course – you want to see the furniture itself. Well, give me a second and I’ll try to dig up some examples for you…

Alright, this is the best I can do:

And another:

Hey, listen, I said they were popular and great quality – I didn’t say you’d be blown away by them.

Anyhow …

By 1867, Jacques & Hay had grown into such a large enterprise that they found themselves needing a bigger showroom. So they built one at Jordan and King:

Here’s that new 176-by-33 foot “warehouse” at Jordan St fleshed out:

Despite the new digs, not long after the company’s move to Jordan, John Jacques decided it was time to hang up his spurs (that makes no sense for an old, British cabinet-maker, but I’m going with it) and retired. In his stead, Robert Hay took two long-time employees into partnership – Charles Rogers and George Craig – and the company was renamed R. Hay & Co. When Hay himself decided to retire in 1885, it then became Charles Rogers and Sons – under which flag it continued to fly into the early 1920s. But, though the furniture was still said to be of good quality, it would never again have the distinction it did when it wore the Jacques and Hay mark.

Ah, but it appears I’ve stumbled a tad far into the future..

Let us now return to the early 1870s, when another important company was moving onto Jordan – the Presbyterian Printing House:

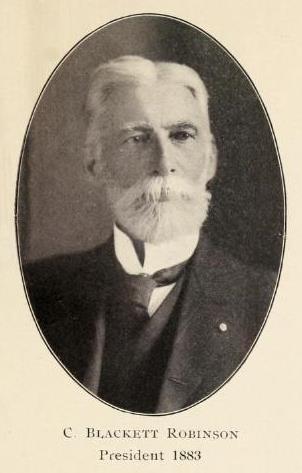

Now, I can appreciate that the name Presbyterian Printing House doesn’t exactly quicken one’s pulse – especially not after all that great cabinetry talk we’ve just had. But believe me, this was a powerhouse in Toronto publishing. And there was just one name behind it:

If you recall our last trip along Jordan St, you might wonder if this was yet another leaf of the Robinson family tree planted up the street in the Wellington Chambers. But no – this was a Robinson of another feather. (Oh hush, I’ll mix my metaphors if I want.)

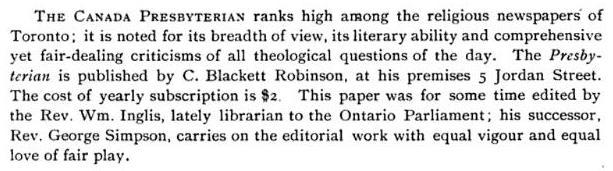

Christopher Blackett Robinson was born in 1837 in Thorah Township – which today forms part of Brock. From the start, he had a taste for the written word – or at least the cutting and shaping of it. At just 20 years of age, he began editing the Canadian Post in Beaverton and he was still at it some four years later when he picked up the paper and moved it to Lindsay. There, over ten years, he guided the paper into one of the highest ranking local weeklies. But come 1871, he was ready to move on. Selling his stake in the Canadian Post, he moved to Toronto and set up a new one called the Canada Presbyterian:

But The Canada Presbyterian was just the beginning. Hot on its heels, Robinson introduced a whole slew of magazines:

But far and away, the work that brought Robinson into the spotlight was that of his biggest contributor – a man named Goldwin Smith:

Goldwin Smith was born in 1823 near Reading, in Berkshire County, England. His father was a physician of some means and so was able to send young Goldwin to Eton, where it was discovered the boy had a great knack for Greek and Latin. From Eton he went on to Oxford where he continued to flourish, winning honours in every subject he competed in. After studying law and being called to the bar, he served as secretary to a Royal Commission, but apparently had no great interest in opening his own practice – preferring to spend his time studying politics and history and writing pieces for newspapers like the Saturday Review.

But then, in 1859, came the call to return to Oxford. Not as a student of course – he was 36 years old at the time – but as staff. Specifically the Regius Professor of Modern History.

Despite being well-liked and a popular lecturer, he was not all that content with the job. Even so, he stayed on at the school until 1866, when his father’s declining health helped guide him to the exit. Submitting his resignation, he headed home to care for his father.

Alas:

With his familial duties now sadly concluded, Goldwin weighed his options. Though he was offered a nomination to parliament, the idea apparently held no particular allure. More attractive was the idea of travelling to the U.S. – a country whose history and politics interested Goldwin quite a bit. As he was considering this, he met and befriended Andrew White, co-founder and first president of Cornell University. And so it happened that Smith was offered, and accepted, a post as the school’s historical lecturer. After keeping this position for two years – very happy ones at that – Smith then made a decision that he would spend the rest of his life trying to explain to people: He moved to Toronto.

As many times as he explained how it came to be, the story never changed. Here we have it in his own words:

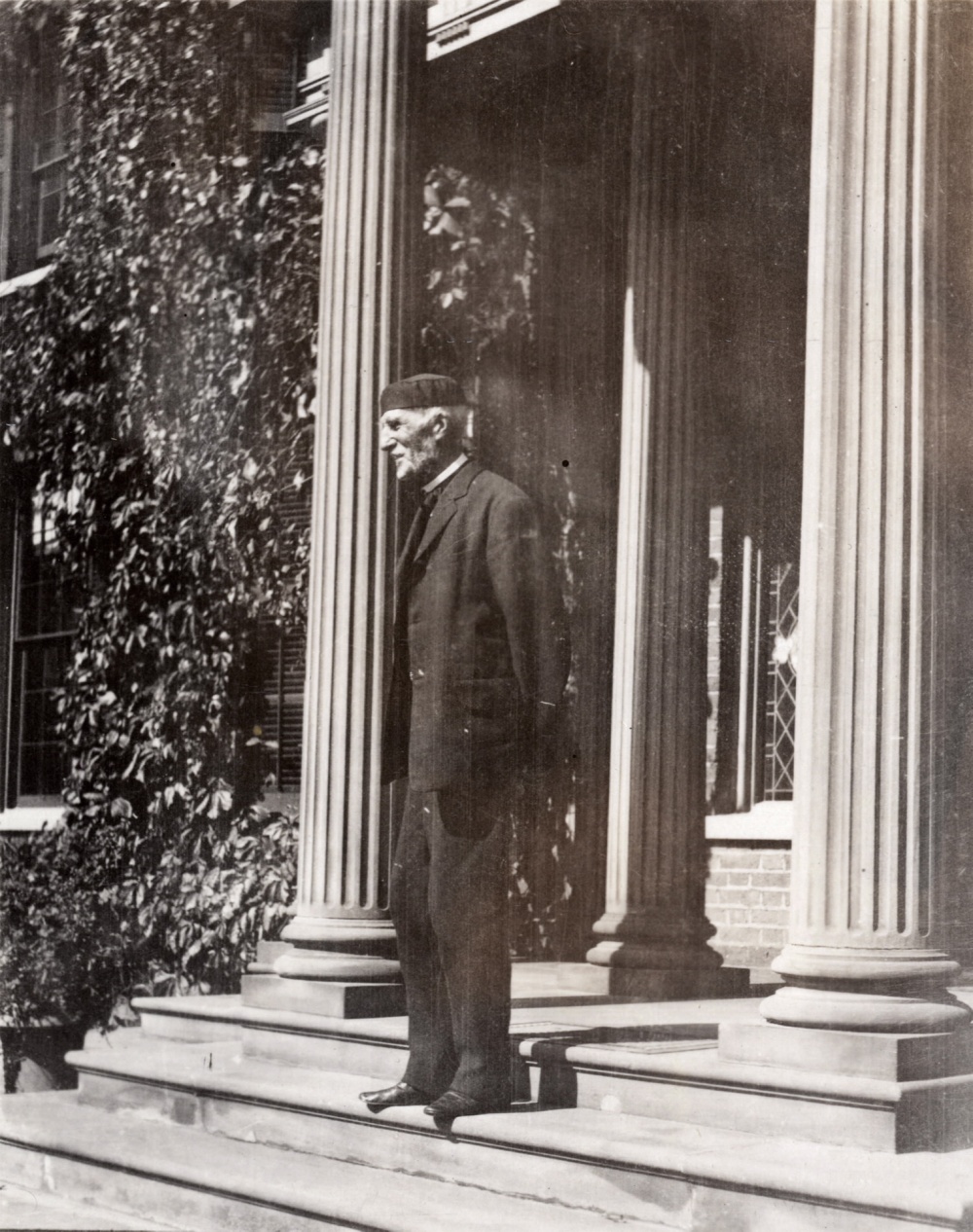

Further strengthening his resolve to stay was meeting and marrying the former Harriette Dixon – Henry Boulton‘s widow – and settling into her grand home, The Grange.

And here we have The Grange in 1867 – better known today for being part of The Art Gallery of Ontario:

In any case, the move to Toronto did not slow Goldwin’s intellectual pursuits in the least. No sooner was he here than he helped get a new paper off the ground – The Canadian Monthly and National Review – for which he wrote under the pseudonym The Bystander:

And of course, he fell in with Christopher Blackett Robinson – an association which would give Smith the job of editing and contributing to a new journal called The Week:

By this time, of course, Smith was already being celebrated across North America and Europe as one of the great minds of the time. And so, having his name on the roster of The Week would’ve been money in the bank. Yet, here in Toronto he wasn’t embraced all that warmly. Oh sure, many residents were proud to count him as a fellow Torontonian. But the old guard that ran the city? Well, they found his ideas and opinions distasteful, to say the least. Take for instance his stance on the American Civil War – why, for goodness’ sake, the man had actually supported the North.

“… Wait – what?” you might be thinking. Yep, that’s right – support of Abraham Lincoln and the Union was a rare thing here. At the time, many were pro-South, i.e. Confederate:

Wilder still was Smith’s belief that Canada’s involvement in the (highly romanticized) Boer War was wrong:

But the topic which got him the most press, and made him the target of The Globe’s George Brown, was the fact that Goldwin Smith was an annexation-man. Annexation being, of course, the movement of the mid-to-late 19th century which sought to unite Canada and the United States. Naturally, this movement was particularly appalling to the country’s big wigs who were fervent in their loyalty to the crown. And so, of course, the idea that Goldwin Smith, a man born and raised in England, should support such a thing was worse than appalling to them – it was treason.

But the thing is, no one else really seemed to care – including the British. Goldwin would travel back to England for a visit each year and continued to be well-received. And so, the only real action that ever came of it all was that the St. George’s Society – of which Smith was a leading member – tried to kick him out. But even that proved tricky as their own policy clearly stated that, as a charitable association, politics could never enter into the mix. Also, it would’ve meant returning all the money Smith had given them – and of course no one really wanted to do that. And so there’s wasn’t much Brown and his cronies could do but write the occasional nasty note about him in their papers:

And so, Goldwin Smith – only mildly irritated by all the bother – would go on writing about and supporting all his wild interests, and living a perfectly contented life at The Grange, right up until his death in 1910 at 87 years of age.

George Brown, on the other hand, did not have such a happy end. Shot on March 25th, 1880 by a recently fired employee, Brown would eventually succumb to the wound nearly two months later, after it’d become gangrenous.

Notably, after Brown’s passing, The Globe would adopt a friendlier view of Smith:

As it happens, it is The Globe itself which brings us to the next chapter of our story…

In 1891, The Globe – forced from its roost on King St – moved to the corner of Yonge and Melinda.

This is what that marvelous building looked like:

But about those “modern improvements” to the building’s heating system …

It was shortly before 3AM on Sunday, January 6th, 1895, when a night watchman making his rounds of the building discovered smoke pouring out of the boiler room. Though he lost no time in raising the alarm, the fire quickly spread to the attic.

Firemen from the Portland and Lombard St fire halls, including the Fire Chief himself – Richard Ardagh – raced to the site, but it was spreading fast.

While the Chief and two firemen, Smedley and Forsyth, inspected the building next door, the rest of the men tried to get close to The Globe with the aerial ladder truck. But the fire continued to build, keeping them from making any progress. As they pulled back in hopes of finding a better angle, there was a sudden, large crash and the entire northern wall collapsed. Falling across Melinda St, it crushed the truck and a young fireman, Robert Bowery, who’d been standing on the ladder. Two men who were unable to get clear of the falling wall, threw themselves under the truck. They were lucky to survive. Looking at the aftermath, it’s hard to imagine how they managed it:

There was now also trouble in the neighbouring building being inspected by Ardagh and his men. Up on the third floor, they were hemmed in by fire and could hear the floors below beginning to collapse. And so, with little alternative, they made their way to a window, shook hands, said “Good-Bye” and jumped. It was a 40 foot drop down to the street. Miraculously, they survived it and were able to crawl along to Wellington where they found a safe doorway to perch in. Smedley and Forsyth would be alright. But Chief Ardagh had been hurt badly in the fall and would die of his injuries three weeks later.

And the fire kept on growing. Aided by the wind, it would spread nearly the entire length of Melinda St before it was finally contained.

Well, if anyone celebrated the end of that terrible fire, they certainly wouldn’t do so for long. Just four days later, on January 10th, 1895, fire visited Melinda once more.

This time someone had set it intentionally.

Beginning in the Osgoodby Building on Melinda, west of Jordan, this fire would stretch all the way down to Wellington St:

Though the Osgoodby fire would prove just as costly and destructive as The Globe’s, thankfully, it would not claim any lives.

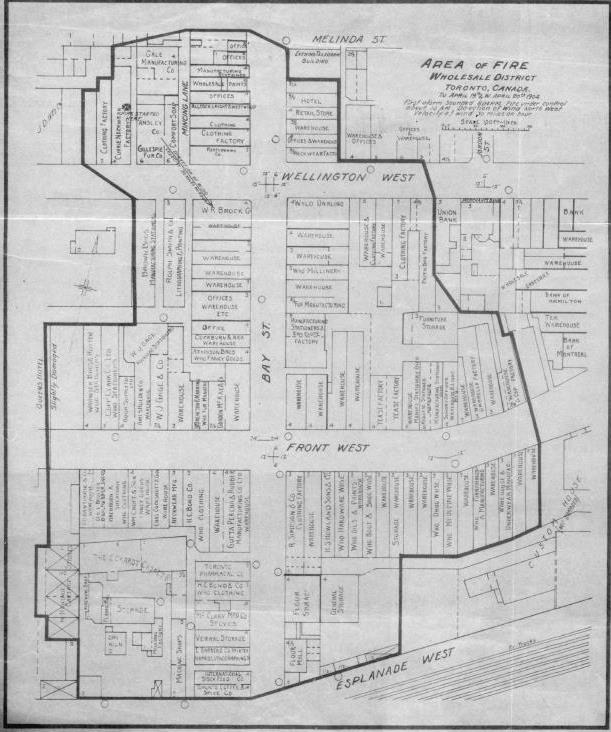

If all this talk of fire now has you thinking of “The Big One” – the Great Fire of 1904 – and wondering how our little neighbourhood fared then, well I’m happy to tell you. Fact is, it came close – really, really close.

As you can see at the top this map, the fire came right up against the Evening Telegram building, which now anchored the west end of Melinda at Bay – yet somehow missed it entirely:

But, while that sounds pretty miraculous, it was actually thanks to a lot of hard work from the Telegram’s staff who’d lined the windows and tossed buckets of water at the blaze.

Here we see the Evening Telegram still standing next to its burnt-out neighbours:

And so the neighbourhood sidestepped being ravaged a third time, and continued peacefully into the 20th century.

While the south side of Melinda remained book-ended by the Globe and Evening Telegram newspaper offices, the north side came to be dominated by the backs of banks and trust companies, whose large buildings stretched south from King. Of these, one – the Canadian Bank of Commerce – would take to the neighbourhood like no other and bury its roots deep.

Knocking down the former Jacques & Hay building at the corner of Jordan and King, it would erect its first grand home in 1893:

But that hefty beauty was soon replaced by this marvel of the modern age:

Lest you doubt an illustration without galloping horses, here it is in the flesh:

As you’ve probably gathered from the above photo, this building yet stands. But it is not the bank’s only home in the Jordan and Melinda neighbourhood.

After the Bank of Commerce merged with the Imperial Bank of Canada, in 1961, a larger, mightier bank was formed and christened the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. (Or CIBC, as it’s now known in our acronym-crazed world.) Of course, bringing the two together under one roof meant building a much larger home. And so it was decided that the block surrounding the Bank of Commerce building would be demolished and cleared to make way for a new complex by I. M. Pei called Commerce Court:

Once all the buildings had been demolished, including the Presbyterian Printing House, an L-shaped swath was laid bare:

With the site now cleared, the developers had a blank canvas to work with. Well, almost. There was still the matter of little Stella Van Zant’s grave…

For over 150 years, the agreement between John Van Zant and Jordan Post to protect her resting place was taken on by all who followed. (Or at least, so it was assumed.) And so, expecting to encounter her grave before long, the bank had a crew of archaeologists brought in to carefully look for her remains. Also invited was the Rev. Walter Gilling, the Dean of St. James Cathedral, to ensure any spiritual aspects were taken care of. Thus prepared, they began their search – at the intersection of Jordan and Melinda.

Here we see the search underway, while a bunch of suits look on:

But they did not find her.

And so the archaeologists packed up their tools, Rev. Gilling went back to St. James and the construction crew resumed their work.

But here’s the thing – noble as their effort was, it’s hard to imagine why they chose the intersection of Jordan and Melinda as their focus. After all, the original document between Van Zant and Post states that the grave was “adjoining the uppermost western corner of the lot of land.” Surely, that would actually mean the area nearer Bay St, just below King:

Having said that, I doubt if a more extensive search would’ve yielded different results. As this area also lay in the path of the new development, I’m certain that – even without archaeologists present – they’d have found her if she were still there.

If I were to hazard a guess, I’d say that with the expansion of the city’s sewer network in the mid-late 19th century, followed by the advent of indoor plumbing, it’s quite likely someone stumbled upon her accidentally. After all, as we’ve found in our visit to Britain St, that sort of thing still happens today.

Of Jordan and Melinda, there is now much missing of the streets themselves. The Commerce Court development swallowed half of each – Melinda lost the block from Jordan west to Bay, while Jordan was amputated from Melinda south to Wellington.

The lost leg of Jordan:

The lost west side of Melinda at Bay:

But while much of Jordan and Melinda were lost to the Commerce Court plan, it must be noted that whole new streets emerged – just not where you’d expect them:

If any ghosts of the old neighbourhood yet wander here, I’ll bet they’re quite confused. Where once they moved amongst ornate buildings that crowded the narrow streets, they now drift across empty, stone spaces and sweep through vast, glass lobbies. Most confusing of all, I imagine, is that there is now more bustling activity below ground than they knew above it in life.

Mangling? My grandmother mangled every Monday using a beast of a machine that could flatten young fingers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! Just as I thought – there’s always a negative aspect to mangling.

LikeLike

I’ve been looking forward to this installment! When I read your posts I always marvel at how much has changed in such a short amount of time. Do you think the inhabitants of a century or two ago could ever have imagined the present state of the city? I’m glad there are those (like you) that take an interest in keeping the facts and stories alive and accessible. Thank you!

(P.S. I’ve been neglecting my own blog, but I found you on Facebook, I’ll catch up with you there, too!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Vanessa! This one truly was a long time coming. Something about it being the last chapter made it particularly tough to write – also there was just so much I wanted to cover.

I think Torontonians of the early 20th century started to have an inkling how things would change. I found a terrific comic warning about towering skyscrapers in 1913, when the tallest building was just about a dozen storeys high. It’s funny to us now, but you can tell they knew their city was really changing.

So glad you found me on Facebook! I’ve missed your posts – you’ve long been one of my favourites 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there is SO much to cover, I can only imagine. But I always appreciate how you manage to weave the bits and pieces together in your posts.

Thank you for your kind words… I haven’t totally gone away… just working on something new. I’ll keep you posted 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh! Looking forward to hearing about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well that was just fascinating! Thanks for finishing it up, I really wanted to find out who the killer was 🙂

Did I ever tell you my dad worked on the Commerce Court project? He was trained as an architect, and specialized as a specifications writer, the person who decides on building materials. He moved from Montreal to Toronto for a year to work on it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

SO happy you liked it! It really was a beast to wrap up. I think I could’ve written a book on the fires alone.

Good grief – I had no idea your Dad worked on it. How incredible! I’d have loved to hear his memories of the project. 🙂

LikeLike

Oh no! It’s not a massive surprise that Stella’s grave disappeared, but I’m still sorry to hear it. I genuinely had no idea that Toronto supported the South during the Civil War! Kind of shocking, since, you know, the whole concept of the Underground Railroad was slaves escaping to Canada and freedom.

Pleasingly hirsute indeed! Marcus has been growing his beard out a bit lately, and I completely dig it. I keep telling him he looks like a salty seaman.

I also agree with the Globe being a marvellous building. That clock tower! Shame it was all destroyed by fire.

And your comment about Mrs. Goldwin Smith and her dog made me laugh. It is an ugly hat, and a good scruffy dog (I’ve been thinking lately that I want to get a scruffy dog and name him Mr. Julius Pringles). And you weren’t even that insulting – it is an ugly hat, and I could have said worse things about Mrs. Goldwin Smith’s attire if I felt like being mean. Oh hell, her dress is real ugly too. It seems too puffy, even by the standards of the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is surprising, isn’t it? Don’t get me wrong, there definitely was a great abolitionist movement here – which George Brown was a part of – but the big names in the city, the old money families (which are still, ahem, celebrated today), they were all for the South. And it’s really kind of appalling.

Ha! Thank you for saying it – it IS an ugly hat. And I agree, that dress is no great shakes either.

I love all dogs but scruffy little guys are the best. And one named Mr. Julius Pringles would send me into fits.

I’m sorry – I steered you wrong. I should’ve mentioned that the Globe building was repaired and continued on for a few decades. (I’ll have to amend that.) But in the end, it was demolished – by choice, which is somehow worse.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Katherine,

Excellent. Well done!

How ar billiard halls?

RL

LikeLike

That photo of the Telegram Building after the great fire with the crowds in front is incredible. Story is fantastic. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

So happy to get your note and pleased as punch to hear you enjoyed the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looking forward to read more blogs & the new book. I am a descendant of John Van Zant & my grandmother wondered about Stella’s fate. She, being of her age, was proud to be a descendant of a United Empire Loyalist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Goodness! How exciting to get your note and learn of your connection to Stella and John. I very much wish I could’ve found a more concrete explanation of the disappearance of her grave. But as with all historical events, additional details may yet come to light.

Thank you again for the wonderful note!

All the best,

Katherine

LikeLike