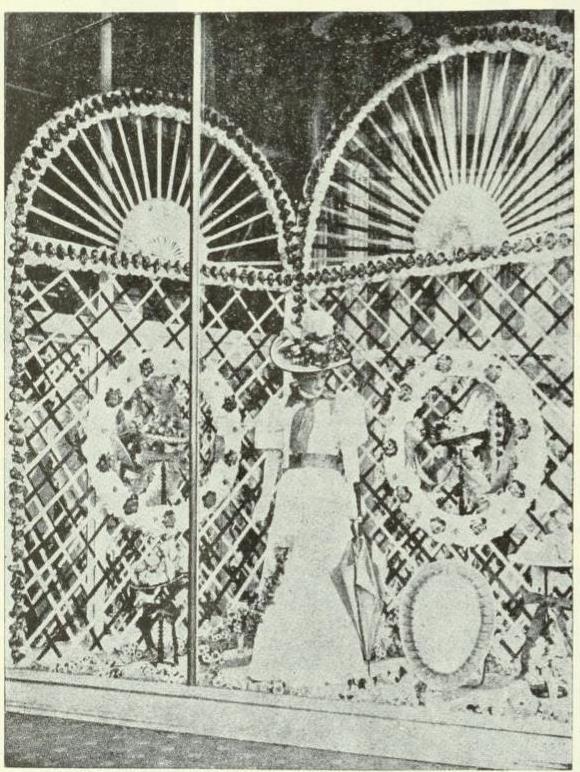

Banner image is of the Murray Kay Co store windows. From the Dry Goods Review, 1912.

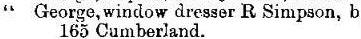

In 1890, with very little fanfare (i.e. none), a man named George Cole, who worked at Simpson’s department store, became the very first person in Toronto to claim the title of “window dresser.”

Sadly, beyond the fact that he lived on Cumberland, next to the Church of the Redeemer Sunday School, and had worked for Simpson’s for several years, I’m afraid I can’t tell you much more about him. Though I can tell you that he gave window dressing as his occupation a full five years before the Merriam-Webster dictionary claims the term first appeared in print. … That’s probably neither here nor there, except to say you can never be sure you’re not getting a bum-steer from your dictionary.

Anyhow… Though George Cole was the first Torontonian to be listed as a window dresser he, almost certainly, was not the only one in town. In those early days, window dressing duties were often assigned to clerks or salesmen – and so it’s quite likely George’s fellow dressers were flying under those other flags instead.

But, regardless of their title, one thing is certain – they all would’ve been male. This is because window dressing was considered heavy work at the time, and therefore outside the bounds of a woman’s abilities. Also, as window displays were set up overnight – and everyone understood that there was only one kind of woman who’d be out, working in the wee hours – it would’ve been thought of as unseemly. And so window dressing would remain a male dominated field for quite some time.

Window dressing itself – or trimming as it would soon be known – wouldn’t really come into its own until the 1890s with the rise of the department store. It was with the building of these grand retail palaces, with their vast plate glass windows and well-lit interiors, that the job would be elevated to something of an art form.

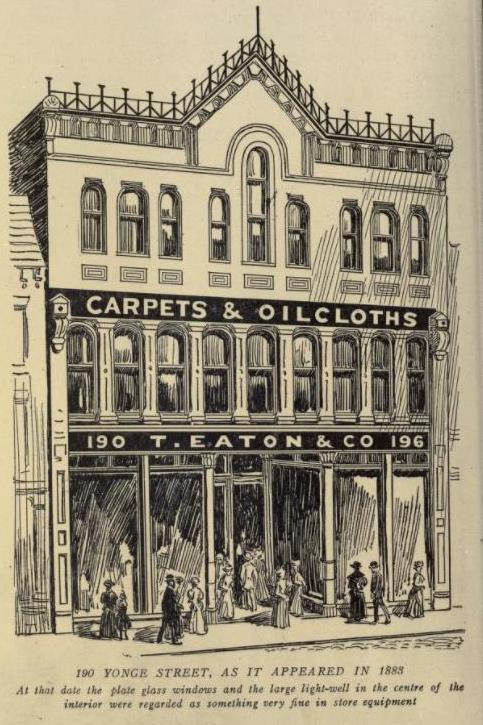

Now, this is not to say that there weren’t interesting window displays in the city before our kings of retail – Timothy Eaton and Robert Simpson – built their great stores. Not at all. As you’ll see, a number of early retailers actually put a great deal of effort into their displays. It’s just that, for the most part, they all employed the same technique. I like to call it the “Here’s everything we’ve got” method:

Even Eaton’s, in its first Toronto home at 178 Yonge, apparently used a version of this technique. In the 1870s, the chief of home furnishings would roll carpet samples out of the store’s upper windows and pin them to the sidewalks below. (Something that makes more sense when you remember the sidewalks were wooden.) And, for a time, this was thought to be a pretty clever way to advertise.

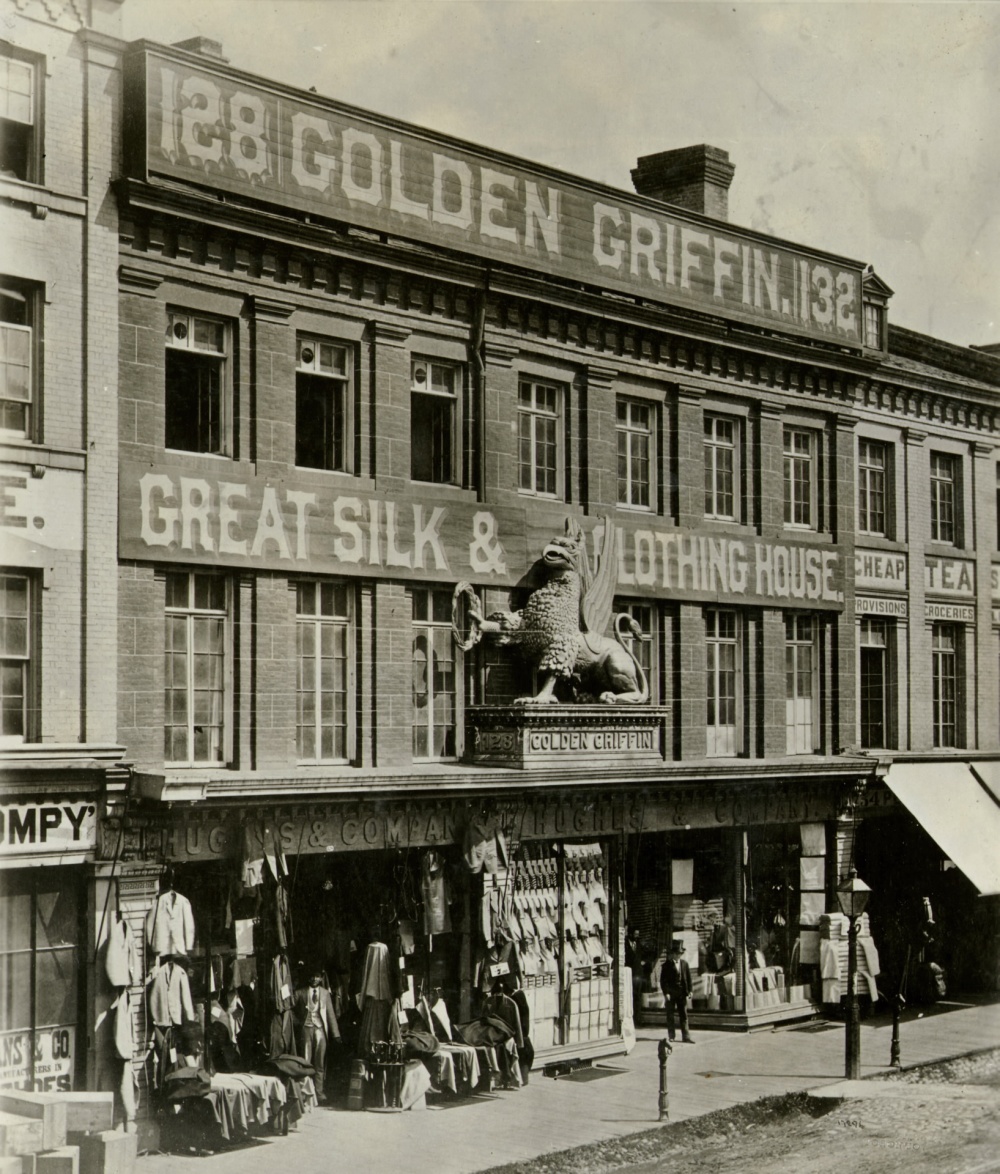

But then, in 1882, Timothy Eaton decided it was time to expand his enterprise and invest in grander digs, and so had a handsome new store built at 190 Yonge.

Once completed in 1883, it had the largest plate glass windows in the city – something all Torontonians with an “eye to civic advancement” could be proud of, according to Eaton. Whether or not they actually were (Robert Simpson’s opinion is not handy) they certainly did have one lasting effect: when the chief of furnishings attempted to unfurl his samples over the windows once more, he was given an earful and forced to retire this particular bit of flair.

Though I should mention that his method would enjoy a brief resurgence, some 36 years later, when Eaton’s thought it a great way to get the attention of a fellow visiting from out-of-town:

But I digress…

With its “carpeting the building” days now behind it (for the most part), Eaton’s set out on a path being taken by department stores the world-over. This new direction sought to woo customers by adding glamour to the shopping experience. Moving away from crowded displays of common goods, stores now used a bit of theatre to create elegant tableaus that not only advertised particular products but also an idealized lifestyle. Done well, the displays would not only sell a customer items they needed but also, hopefully, a luxury item or two they didn’t.

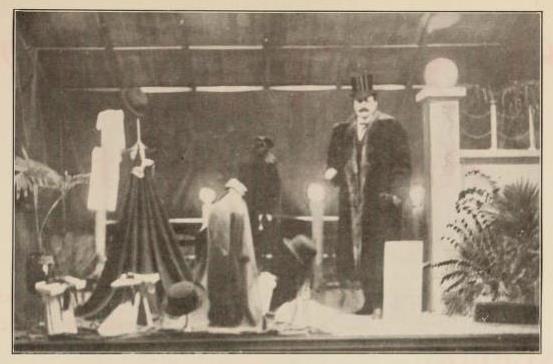

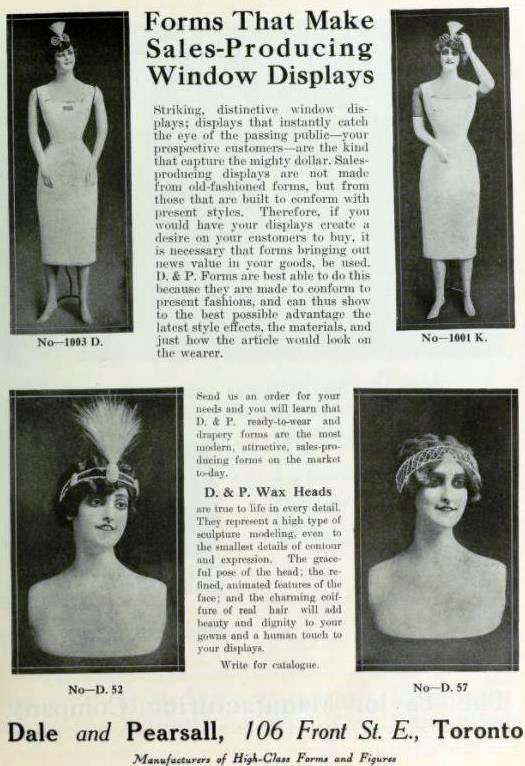

And, naturally, if you wanted to inspire shoppers to buy, well then you had to help them imagine themselves in, or with, the goods. Originally, this was done using dress forms – long a tool of the tailoring trade:

But imagine how much more attractive goods would appear on something a little more human in size and shape – something with a head, perhaps.

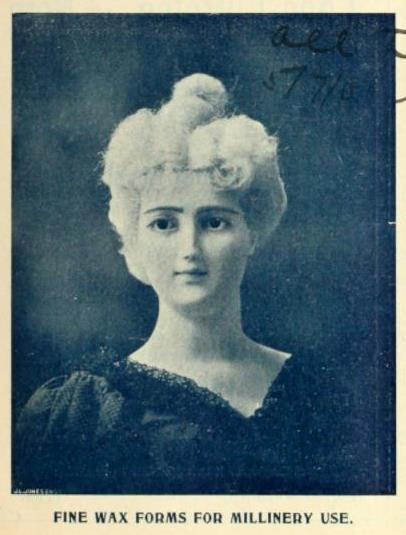

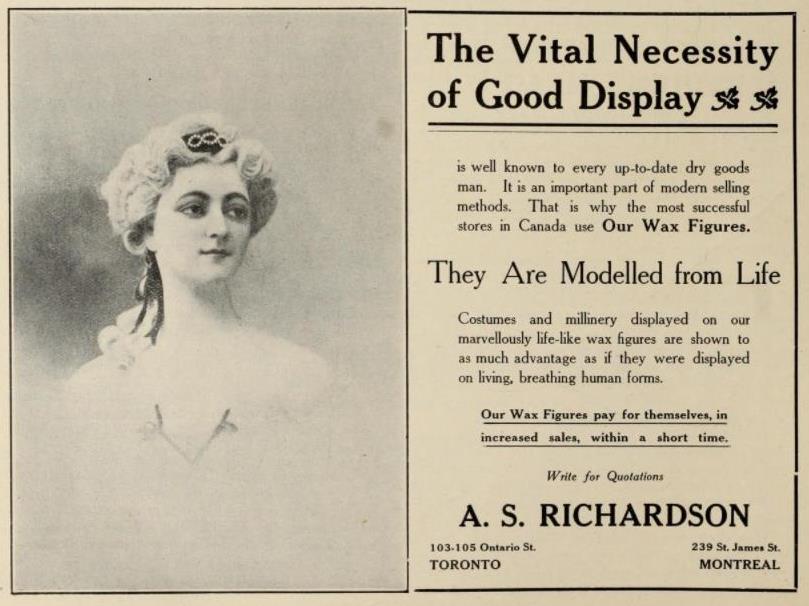

And so the wax figure became an integral part of window dressing furniture:

Though the wax figure first appeared in Paris during the 1850s, it would be roughly 40 years before they became common fixtures in Toronto stores. This delay (if you can call a near half-century that) was due to the fact that the figures were very expensive and difficult to import from France – and even from the U.S., where they were eventually manufactured:

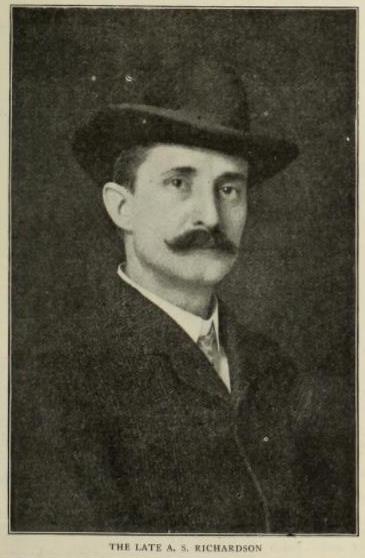

Luckily for Toronto retailers, however, someone local would eventually step up and start churning out his own models. His name was Arthur Richardson and he was our first wax figure sculptor:

Arthur Richardson’s first appearance in the city’s records came in 1884, when he was 22 years old and working for the H. E. Clarke Co – a manufacturer who specialized in trunks and valises. But this work was apparently not his bag (sorry) and the next few years would find him operating a ruling machine at the Copp, Clark & Co print shop.

But then came an interesting turn in his life. In 1890, he began working at one of Victorian Toronto’s premier attractions – the Cyclorama on Front St:

Just the name – Cyclorama – sounds exciting, doesn’t it? Brings to mind wheeled fun – like bicycles or roller skates. Well, I’m sorry to say that no such things went on in there. Instead, the circular building held enormous panoramic paintings depicting things like the Battles of Waterloo and Gettysburg, and Jerusalem at the time of the crucifixion. But folks sure went wild for it. They’d line up to pay 25 cents a pop for the chance to stand on a platform in the center of such scenes and listen to lectures on the subject. Lectures provided by our Arthur Richardson.

Now, whether art and entertainment had always been Richardson’s interest, or if it was this association with the Cyclorama that woke it in him, I couldn’t tell you. But one thing I do know is that after leaving the Cyclorama, Arthur was going his own way:

I cannot tell you how it pains me that I haven’t any gems from Arthur’s foray into magic to share with you here. But the fact that it lasted roughly a year gives some indication of how it went.

Luckily for Arthur (and us) his next venture would prove far more successful:

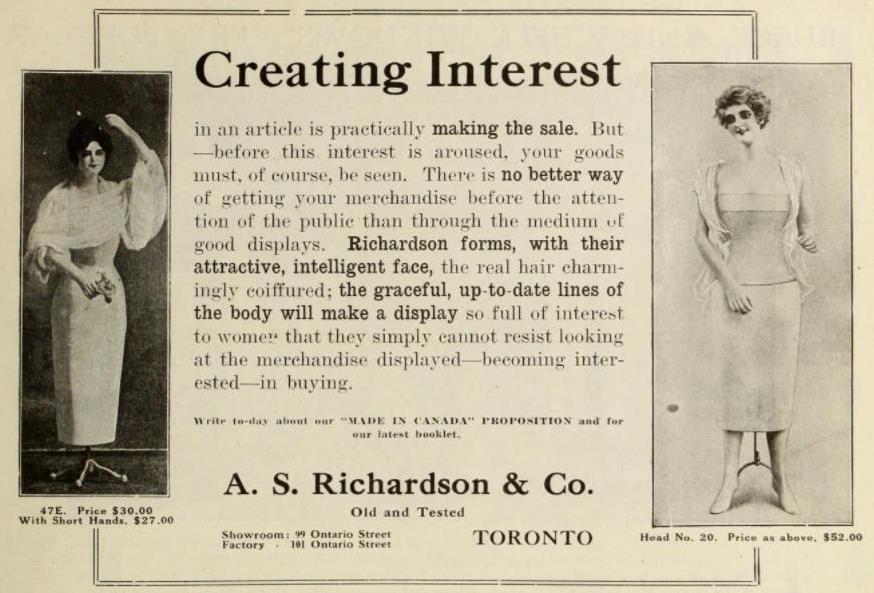

It was with this wax sculpting that Richardson would finally make his mark. Originally working out of his home on Euclid, the business would eventually grow into a storefront on King, then Yonge, before finally taking on a large factory on Ontario St, and even a second in Montreal.

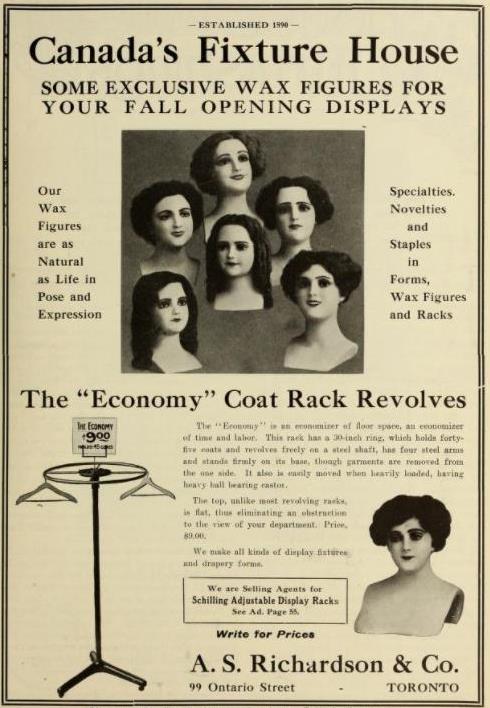

And now, because I know you must be itching to see some of his handiwork, here are some of his wax figures:

And to mix things up a bit – a bunch of brunettes in various states of disbelief:

For those looking for full-bodied figures – which, by the way, could weigh as much as 300 lbs – there were these beauties:

Sadly, Arthur Richardson’s run would be much shorter than that of his business. He’d die in 1909 at just 47 years of age. Following his death, the business was carried on by his wife, Mae, for a time until finally being shuttered in 1920.

Of course, while Arthur Richardson was our first figure maker, he was hardly the last. Not long after he started churning out his waxen army, two other companies emerged, looking for a cut of the action: George Clatworthy & Co and Dale and Pearsall:

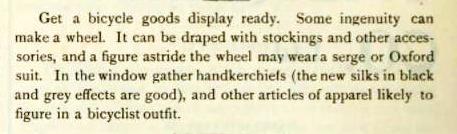

Do you feel like we’ve seen enough of these things? Good. Because now that we’ve had a look at the available models, I’d like to share with you some brilliant ideas which the Dry Goods Review – the window dressers’ bible – offered for their use:

Of course, now you’re wondering (c’mon, play along – you’re wondering) “These are just ideas. What were our actual windows like in Toronto?”

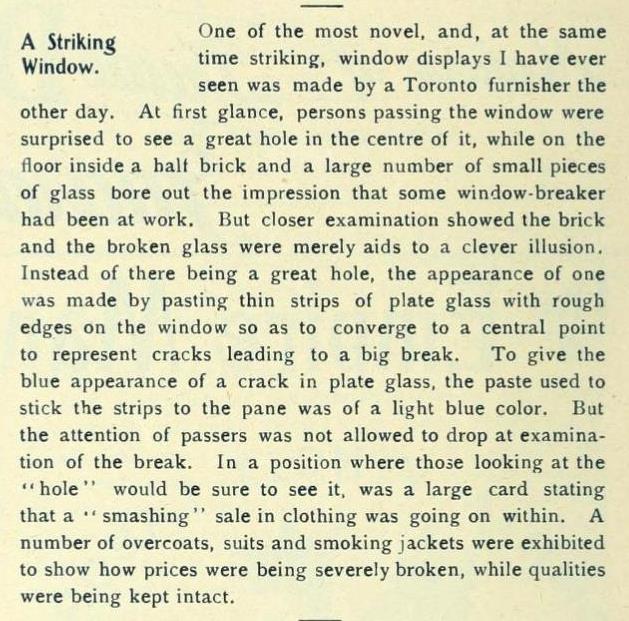

Well, here’s one that saw the light of day:

And another that I really wish I’d been there to see:

And so you begin to see how window dressing moved out of the realm of a clerk’s duties and into a full-fledged job of its own. Each window not only required a good amount of imagination, but also some pretty serious planning and construction. Everything had to be built, hung, papered and painted by the dresser, who also had to have an understanding of fashion – not to mention, be a deft hand at card writing:

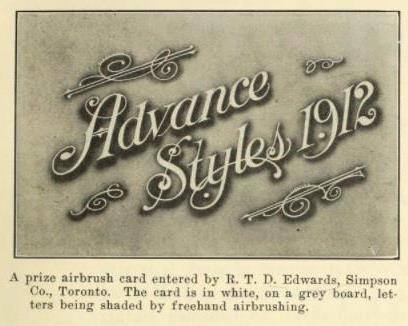

In case you’re wondering what a good example of card writing might look like, this is the sort of thing they were looking for:

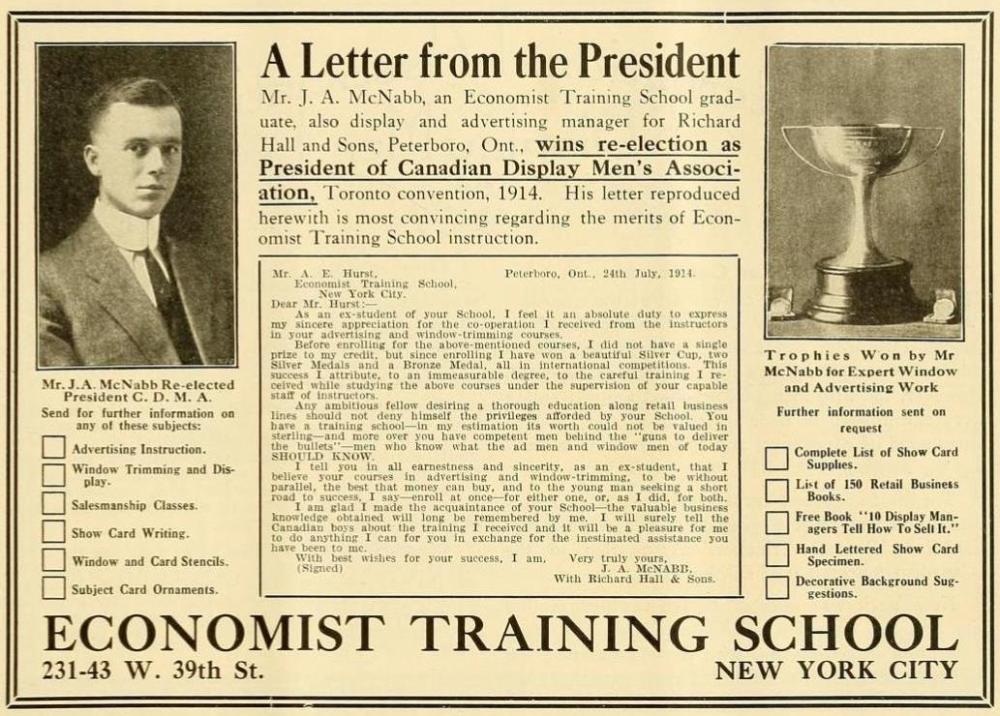

So, yeah, there were a lot of ins and outs to window dressing and it’s a fair bet that not all were born to the trade. Happily, for those folks who were lacking in one or more of the key areas, there was a school in New York that would help you harness your inner potential. And who better to advertise its winning aspects than the very President of the Canadian Display Men’s Association? Peterborough’s own (pardon me, Peterboro) J. A. McNabb:

That’s right – there was such a thing as the Canadian Display Men’s Association. Though when originally formed, around 1900, it was known as the Canadian Window Trimmers Association. But of course, the name’s not important – the important thing is that they were a brotherhood and that they’d get to have conventions.

In fact, their very first convention was held here in Toronto at the Prince George Hotel in August of 1912. And what a remarkable event it must’ve been – not least because they managed to get three days out of it.

And here are the happy convention goers themselves:

While I imagine that meeting trimmers from all over Canada and seeing examples of innovative merchandising fixtures were the highlights of these conventions, the subsequent reports really only focused on the key messages of each event.

For instance, here’s what the 1912 convention boiled down to:

And here’s the rather wonderful theme of trimmer A. E. Hurst’s speech at the 1914 convention:

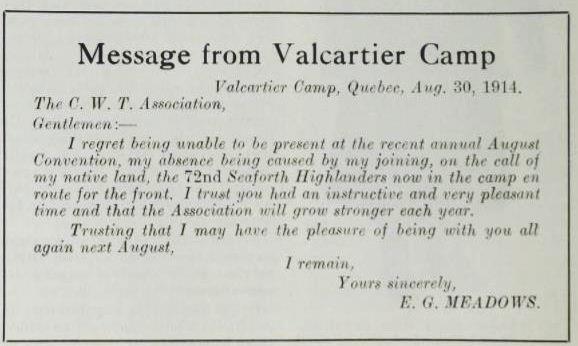

But with the onset of WWI, a number of window trimmers would enlist and, as a result, conventions after 1914 saw attendance dwindle.

You’d imagine then, that with so many trimmers off overseas, women would finally be welcomed into the fold. But, surprisingly, this wouldn’t really happen until the 1940s, with the next World War.

With women now working to keep a number of vital industries humming, including the truly heavy, dangerous work of munitions factories, I imagine window dressing suddenly seemed like rather “light work” by comparison.

Today, window dressing is as important to the retail trade as it was when Eaton’s installed its beloved plate glass windows in 1883. If anything – given this age of online shopping, and its effect on bricks and mortar retailers – I imagine it might be even more important. And so it’s no surprise to find that window dressers and their associations still exist. Though, of course, it’s no longer called window dressing, or even trimming. Today it’s “visual merchandising.” And, like the delightful Dry Goods Review of yore – which I’ve drowned you in today – there’s even a magazine devoted to the industry: VMSD (Visual Merchandising Store Design). Also, happily, there’s still an annual convention (now called a “conference”), as well as an International Visual Competition.

So name aside, I don’t imagine too much has changed in the industry. Oh sure, no one uses wax figures anymore (it turned out they didn’t age well in sunny windows) and it’s not often you’d have to airbrush your own cards these days – but I’m sure many of the original principles and techniques remain the same. Though, somehow, I have the feeling not one of this modern crop would mind being considered “an artist.”

A fascinatingly oblique look at Torontonian life (Torontonian?) and what impressive research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Reggie! And you’re right – believe it or not, we do say “Torontonian.” Though it seems a bit cumbersome at first, it trips off the tongue after a few goes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This one was a lot of fun to read, and it must have taken you some time to research and write!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so happy you found it fun, Susan! I had a great time researching this one – though it did take some time. My eyes will be happy for a rest now 🙂

LikeLike

Enjoyed reading this post. I can just imagine how much research went into finding the historical images and facts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so happy you liked it, Patti! That means a lot to me.

LikeLike

You wax poetic! Great as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you liked it! Gifford’s up next!

LikeLike

Oh, I’m so happy to see a post from you! And a great one, too. The “Here’s everything we’ve got” method – LOL – it really applies today, too, in the digital age. We want websites to be clean and attractive and easy to navigate and we love seeing what’s on sale first, but as soon as a site is too cluttered and unorganized, we’re outta there 🙂 It’s so intriguing how things evolve over time. Thanks again for another awesome post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, thank you, Vanessa! I’m so happy you enjoyed this one.

You make a great point about display being a digital concern too – I hadn’t considered that. But you’re so right – I’ve definitely passed on a site for the very reasons you mention.

Thank you, as always, for stopping by 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this so much! And I’m so happy that you included a history of wax models, and so many pictures of said models, especially since I know they give you the creeps! The mouth on those Dale and Pearsall models kills me, though I would definitely wear the headbands (possibly with my flapper dress, even though they’re not from quite the same era). I like the cut of Arthur Richardson’s jib too, and I definitely love his creepy wax figures – I feel like they’re staring into my soul! I would also love to see most of the displays mentioned here – my local department store had these weird giant pancakes and frying pans in the window for Pancake Day, and I thought that was really pretty impressive, but nowhere near the level of storks or mannequins riding bikes. I am equally perplexed by “short hands” (seriously, wtf?) and I love that you managed to work a Seinfeld quote in. Hilarious perfection throughout!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, hooray! I’m so glad you liked this one! I thought of you as I was researching it. You’re one of the few people I know that finds mannequins fascinating – also, you may be the only person who knows how they give me the willies.

Yeah, the mouths on those Dale and Pearsall figures are really, uh, something. I showed them to my mother and she laughed and laughed. But I agree about their headbands – you should definitely look into getting one. It’d be a great stand-in till you can get the cloche-style hat.

I’m so glad you like Arthur Richardson too. I’m a little sweet on him now. And his wax figures are definitely my favourites – and you’re right, they’re totally looking into your soul.

Wow, that pancake and frying pan window sounds fun! I’d love to see something along those lines here. As much as I know “visual merchandising” is a going-concern, I just don’t see that much inventiveness out there. Though to be fair, I’m not much of a shopper, so it’s possible I’m just missing out on a lot of window dressing magic. (Note: I doubt it.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I’m flattered that you thought of me, if only because I’m so weird! Wax figures are fantastic though, precisely because they are so creepy.

The department store with the pancakes seems to change their windows quite a lot, and some of the designs are pretty good. I can’t say it makes me shop there though – all their stuff is expensive, and not really to my taste.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the old storefronts with their nicely dressed windows. You can still see such storefronts in Cobourg and Bowmanville, two towns I love, and on some streets in Toronto too, right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love them too – they can be such a delight. I’ll definitely have to stop in for some window-shopping in Cobourg and Bowmanville soon. And I imagine there are some lovely old buildings to enjoy too 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey there! I came across your work as it is one of the *only* places I seem to find mentions of Clatworthy & Co. Do you have any links to further information about the company and its history? I’m from Saskatchewan, so I can’t just pop into a local library!

LikeLike

Hi!

Clatworthy & Co was founded in 1896. There’s some additional information on the company available in the 1906 Dry Goods Review – page 56 – which you can view here:

https://archive.org/details/dgrstyle1906toro/page/n295/mode/2up?q=Clatworthy+

LikeLike